Farm & Ranch

Dr. Jason

By Ddee Haynes

“We make a living by what we get. We make a life by what we give.”

Winston S. Churchill

The words of Winston Churchill could not ring truer to a person’s character than to Dr. Jason Thorne, DVM.

I first met Jason (aka Dr. Thorne) while on a field trip with the Custer County 4-H horse club about seven years ago. Jason was fresh out of vet school and working for a local clinic. I am pretty certain he was still considered the low man on the totem pole, thus the reason for him being chosen to visit with a group of lively 4-H kids. As a mom of one of those kids, I was extremely impressed how Jason handled all the questions that were thrown at him, how he took time to show the kids around the clinic and overall made the entire experience a huge success.

Jason’s demeanor and sincerity that day left a lasting impression on those kids and I couldn’t help but chuckle to myself as I listened to the conversations on the way home as a few of the young girls talked about what they had learned that day and “how cute” Dr. Thorne was.

Growing up in Marlow, Okla., as the son of the Police Chief, Jason once considered following in his father’s footsteps, but his love for animals kept pulling him in a different direction. When his dad began adding longhorns to his herd, Jason had the idea to start training them to ride. Jason would choose which longhorn to train as to which animal would first come up to him. Jason stated that gaining the trust of the longhorn was important, but building their trust was the key. Once a longhorn pupil was chosen, Jason would become the only person to have contact with the animal, even pulling it from the herd. The longhorn would come to rely solely on Jason. During his high school years, Jason trained several longhorns to ride and would later sell them.

In addition to his love for animals Jason enjoyed playing basketball and football. However, when he later transferred to a larger school, he found that sports were taking time away from his true love, animals. Jason’s career path was determined after a “Career day” allowed him to work alongside Dr. Holly Wilson at Beavers Animal Hospital in Lawton, Okla. At the time Jason was 15 years-old and happened to be at the hospital while Dr. Wilson was preforming a C-section on a greyhound. Dr. Wilson showed Jason how to clear the fluid from the pup’s lungs. Thanks to Dr. Wilson and Jason, all four pups survived and the career path for Jason was clear.

Jason graduated with his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from Oklahoma State University, Stillwater. Okla., in the spring of 2010. Jason took his first job at a clinic in Western, Okla., where I first met him on the 4-H horse club field trip. Little did I know after meeting Jason that afternoon that he would become a huge part of our family, not just as the DVM for our animals but also as a friend.

In 2016, Dr. Jason and his wife Lacey decided to take a leap of faith and go out on their own. They purchased a vet trailer and hit the ground running. It did not take long before Jason’s reputation, work ethics and true love for animals spread around the countryside. Jason soon became the go-to-vet for cattle ranchers, horse lovers and, of course, the small animal cliental.

Our family had started using Jason for horse vaccinations and maintenance, but it wasn’t until one almost fatal night that we saw just how much this young vet truly cared for his four-legged patients. The weather had turned off cold and wouldn’t you know it, one of our horses was showing signs of colic. As I prayed for our horse, Magic, I dialed Jason’s cell. When Jason answered I explained the symptoms and he assured me he was on his way.

Sure, enough Magic was impacted, dehydrated and on her way to a full-blown colic. Jason worked patiently administrating fluids all the while touching and speaking to Magic in a calm and soothing way. After the first bag was emptied, he still did not feel Magic was good and decided to give her another bag of fluids. By this time, it was close to 11:00 p.m. and pretty darn cold even inside the barn. Jason told me to go inside and that he would stay with Magic. He said he had paperwork to do and could sit inside his truck and work while keeping an eye on her. Although I offered to stay with him and Magic, he insisted I go inside. A few hours later, Jason texted me. Magic was going to be fine and he would check on her the next day. True to his word, he not only called but also came out to look at her again.

Over the past few years we have had other emergencies as well as non-emergency issues with our animals. Each time Jason has gone above and beyond. After my favorite dog Pete was chewed up by coyotes in the wee hours of a Sunday morning, I waited until after 8:00 a.m. that morning to call. Jason told me to load up Pete and meet me at his home. Once again Jason saved the day and Pete survived. Although I do believe Pete still holds a grudge for Jason calling him fat! Come on, Jason, Pete is just big-boned.

When Jason decided to strike out on his own, Lacey supported his decision and took the leap of faith with him. Together they have worked alongside one another to establish Territory Medicine, located just west of Weatherford, Okla. Both Jason and Lacey have made many sacrifices to make their dreams a reality. While Jason worked long hours, Lacey gave up family time with him. For over a year the young family lived in a 5th-wheel trailer with their two small children inside what is now part of the clinic.

Jason, Lacey and their two young daughters Aysa and Aspyn now make their home over the clinic in a home they literally built themselves. Territory Medicine is booming. Although his business is continuing to grow, Dr. Jason still makes each patient and their owners feel as if they are his only priority.

I whole heartily believe the old saying “If you love your job you will never work a day in your life.” Dr. Jason Thorne is a perfect example of loving his job. Keep up the good work, Dr. Jason, and thank you for all you do!

Until next time….

Read more in the January issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Inventions of Agriculture: The Reaper

Agriculture has been a staple of human society since around 9000 BCE during the Neolithic Era, when humans began developing and cultivating their own food.

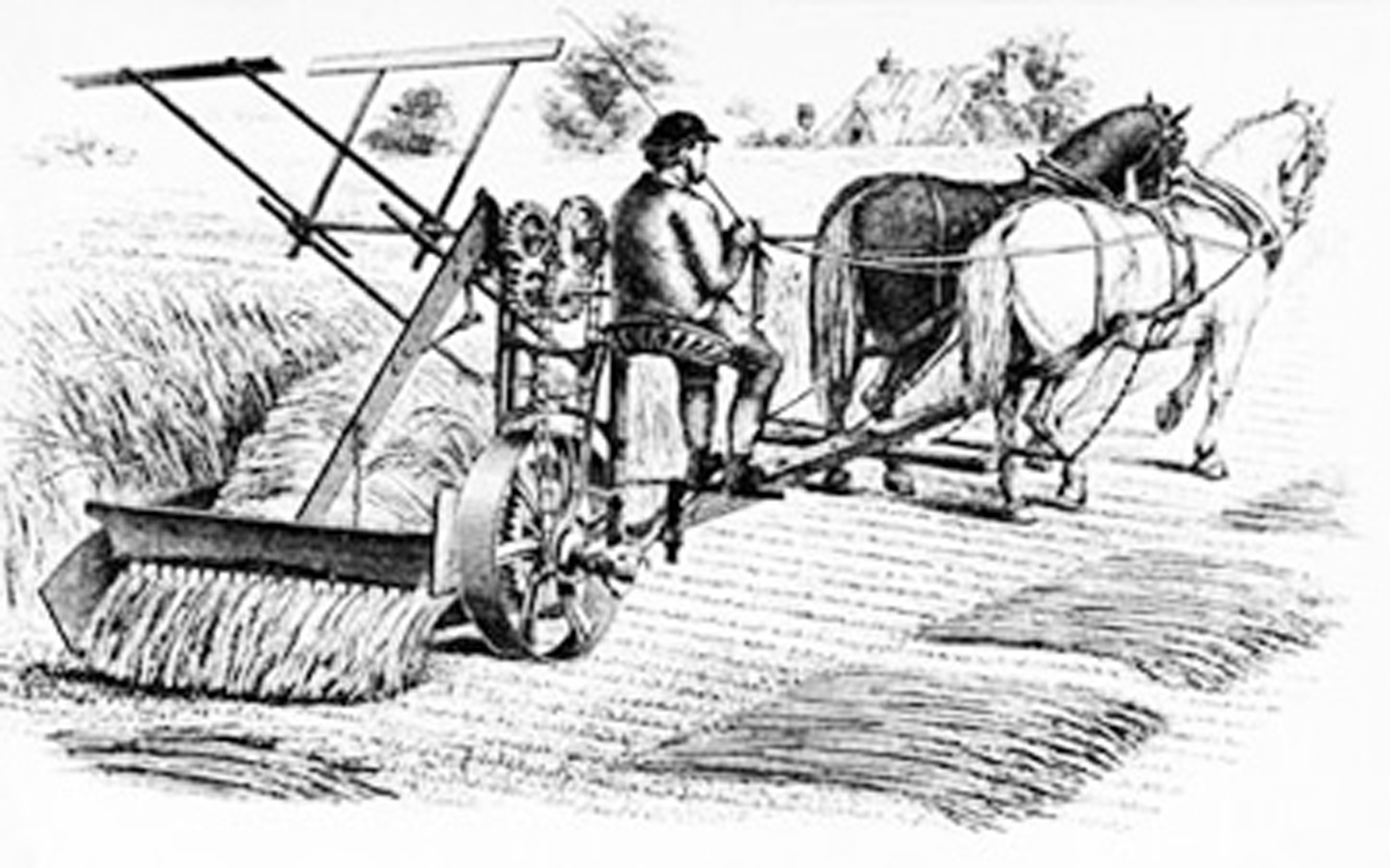

For centuries, food production was a slow, tedious process until the invention of agricultural machinery. One such invention was the reaper. Until its time, small grains were harvested by hand, cut with sickles or scythes, hand-raked and tied into sheaves.

While a few had unsuccessfully attempted to create a similar machine, it was Cyrus McCormick who would ultimately be credited with the invention of the first commercially successful reaper in 1831.

McCormick’s invention was a horse-drawn machine used to harvest wheat, a combination between a chariot and a wheelbarrow. He had joined together the earlier harvesting machines into a single, timesaving one. His reaper allowed producers to double their crop size, capable of cutting six acres of oats in just one afternoon. In contrast, it would have taken 12 workers with scythes to do the equivalent in the same amount of time.

McCormick had simply followed in his father’s footsteps. Growing up in Rockbridge County, Virginia, his father had also created several farming implements and even worked to invent a mechanical reaper of his own.

McCormick would patent his invention in July 1834, a year after Obed Hussey had announced the making of a reaper of his own. In 1837, McCormick began manufacturing his machine on his family’s estate.

In 1847, McCormick recognized Chicago as the future of the agricultural machinery industry. The railroad to Galena was nearing completion, the Illinois and Michigan Canal would soon be open, and a telegraph link to the east was coming. So, in 1847, McCormick, together with his partner and future Chicago mayor Charles M. Gray, purchased three lots on the Chicago River and built a factory where they would produce the reaper. It was the first of many industrial companies that would make their way to the area, making Chicago an industrial leader.

McCormick wasn’t done yet. He purchased an additional 130 acres in Chicago in 1871, but the Great Fire of 1871 threatened to destroy his company when the factory burned. It was his young wife, Nettie Fowler McCormick, who pushed the company forward when she went to the site just days after the fire and ordered the rebuilding of the factory. By 1880, McCormick was the largest machinery producer in Chicago and employment reached 7,000, a whopping fifth of the nation’s total.

McCormick joined the companies of Deering and Plano to form the International Harvester Company in 1902. At its height, the company controlled more than 80 percent of grain harvesting equipment in the world. While the Great Depression would hit Chicago’s agricultural industry hard, McCormick’s invention of the reaper forever changed the face of agriculture.

Resources

Carstensen, Fred. (2005) Agricultural Machinery Industry. Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/29.html

Cycrus McCormick, Mechanical Reaper. (2022) The National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved from https://www.invent.org/inductees/cyrus-mccormick

Although the author has made every effort to ensure the information in this article is accurate, this story is meant for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for historical documents.

Farm & Ranch

Scrapie

Barry Whitworth, DVM

Senior Extension Specialist Department of Animal & Food Science Ferguson College of Agriculture

Scrapie is a chronic, progressive disease of the central nervous system that affects sheep and goats. Scrapie is the oldest of the group of neurodegenerative diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE). Some of the other TSE are Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy known as mad cow disease, Chronic Wasting Disease which is found in deer, and Creutzfeldt Jacob Disease which is found in humans. TSE are protein-misfolding diseases that lead to brain damage and are always fatal.

The cause of Scrapie is not completely understood, but evidence indicates that an infectious protein referred to as a prion is responsible for the disease. These infectious prions cause damage to the normal prion proteins found in the brain. The mis-folding of the proteins lead to brain damage and the presentation of clinical signs of the disease. Prions are very resistant to destruction, so once in the environment, they are difficult to remove.

Scrapie is believed to primarily be transmitted by the oral route. Typically, lambs and kids might ingest the prion when they come in contact with the infectious agent through placentas and birthing fluids from infected ewes and does. Older animals may be exposed to the prions this way as well. Colostrum and milk are also sources of prions. Other secretions such as urine, feces, saliva, and nasal secretions may contain infectious prions as well. Once ingested, the prions cross into the lymphoid system. The prions will incubate for a long time usually two to five years before entering the nervous system.

Genetics plays a part in Scrapie infections. Certain breeds are more susceptible to the disease due to genetic composition. Genetic testing is available for producers to help them select breeding stock with resistant genes.

Clinical signs most commonly associated with Scrapie are intense pruritis, ataxia, and wasting. Early in the disease, small ruminant producers may notice slight changes in behavior with sheep and goats infected with Scrapie. Initially, animals may have a staring or fixed gaze, may not respond to herding, and may be aggressive towards objects. As the disease progresses, other clinical signs noticed are progressive weight loss with normal appetite, incoordination, head tremors, and intense pruritis. In the terminal stages, sheep are recumbent and may have blindness, seizures, and an inability to swallow. Once initial clinical signs are notice, death usually occurs in one to six months.

The gold standard for postmortem (dead animals) diagnosing of Scrapie is the use of immunohistochemistry test on brain tissues as well as microscopic examination of brain tissue for characteristic TGE lesions. Live animal diagnosis is possible by testing lymphoid tissues from the third eyelid and rectal mucosa scrapings.

There is no treatment available for Scrapie, so prevention is key to controlling the disease. Following biosecurity protocols is a good starting point for preventing Scrapie. Part of the biosecurity plan is to maintain a closed flock and only buy replacement animals from certified Scrapie free flocks. Producers should limit visitors’ contact with their animals. Sanitation is important in lambing and kidding areas. Manure and bedding contaminated with birthing fluids and placentas should be disposed of properly. Genetically resistant animals should be used for breeding to produce genetically resistant offspring.

It should be noted that there is a novel or atypical form of Scrapie. This disease may also be referred to as Nor98 variant. This atypical version of Scrapie was initially found in Norway. It has been diagnosed in the United States as well. The disease is usually only found in a single old animal in the flock or herd. The brain lesions in atypical Scrapie are different from classical Scrapie. Currently, experts believe that natural transmission of atypical Scrapie is not likely.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been battling Scrapie for decades. According to recent information from the USDA, the United States (US) is close to accomplishing eradication of the disease. In order for the United States to achieve Scrapie free status, no sheep or goats can test positive for classical scrapie for seven years and a certain level of testing needs to be done each year that represents the sheep and goat populations within the country. Small ruminant producers can assist the USDA eradication efforts by contacting the USDA when they have an adult sheep or goat exhibiting clinical signs of Scrapie or an adult animal dies or is euthanized. Producers should contact the Oklahoma State Veterinarian, Dr. Rod Hall at 405-522-6141 or the USDA Veterinary Services at 405-254-1797. This will aid the USDA in reaching sampling testing goals. There is no charge for the collection or testing of the samples for scrapie.

Scrapie is a disease that needs to be eliminated from the US. Once eliminated, the US will have additional export markets for sheep and goat products. Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Service has an informative fact sheet on Scrapie. Please visit the Local County Extension Office and asked for fact sheet VTMD-9135 or producers may view the fact sheet online at https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/scrapie.html. Also, the USDA National Scrapie Eradication Program website has valuable information as well at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/sheep-and-goat-health/national-scrapie-eradication-program.

References Cassmann, E. D., & Greenlee, J. J. (2020). Pathogenesis, detection, and control of scrapie in sheep. American journal of veterinary research, 81(7), 600–614. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.81.7.600

Farm & Ranch

Avian Influenza Update

Barry Whitworth, DVM

Area Food/Animal Quality and Health

Specialist for Eastern Oklahoma

High Path Avian Influenza (HPAI) continues to be a problem in commercial and backyard poultry in the Unites States (US) with over 60 million birds affected. Since the start of the outbreak in 2022, 879 flocks (347 commercial and 532 backyard flocks) have been confirmed with HPAI in the US. Many wild birds and mammals have been affected as well. Five backyard flocks and one commercial flock have been confirmed with HPAI during this outbreak in Oklahoma. The latest was detected in a backyard flock in Carter County on October 16, 2023. For a complete listing of domestic birds, wild birds, and mammals affected by HPAI visit 2022-2023 Detection of High Path Avian Influenza website at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/avian-influenza/2022-hpai.

Avian influenza (AI) is a highly contagious viral disease. The virus is classified as either Low Path Avian Influenza (LPAI) or HPAI depending on the virulence. This virus infects many food producing birds such as chickens and turkeys while it commonly resides in migratory waterfowl and many other wild birds. Most often ducks, geese, and wild birds harbor the virus in the intestinal tract without having any clinical signs of the disease. The virus is shed in the feces and respiratory secretions from infected birds. Poultry can be infected with the virus when they come in direct contact with infected birds or consume feed that is contaminated with the virus. The virus can be spread indirectly through objects like shoes, clothes, or equipment contaminated with the virus.

Clinical signs of the disease vary depending on the severity of the virus and the organ system affected. LPAI usually results in no clinical signs or only mild problems. However, HPAI has many different clinical signs. Death with no symptoms is a common finding. Respiratory problems such as coughing, sneezing, watery eyes, and nasal discharges may be seen. Depression resulting in loss of appetite and decrease consumption of water may occur. Egg production may be impacted with a decrease in production and/or softshell or misshapen eggs. A bird’s comb, wattle, head, eyelids, and hocks may swell. Combs and wattles may turn purple. Nervous system disorders including tremors, incoordination, and unusual positions of the head may be seen. Diarrhea has been reported in some cases. For more information about clinical signs visit Defend the Flock-Signs of Illness at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/avian/defend-the-flock-program/outbreak-illness/outbreak-illness.

For commercial and backyard poultry flocks, the best defense against HPAI is a sound biosecurity program. Biosecurity is the development and implementation of management procedures intended to reduce or prevent unwanted threats from entering a flock. The protocol is designed to reduce or prevent the spread of unwanted threats through the flock and eliminate any unwanted pathogens that may enter the flock. Lastly, a biosecurity plan is designed to prevent threats from infecting neighboring poultry operations. Biosecurity can be broken down into four basic areas which include traffic, isolation, sanitation, and husbandry.

The first line of defense should be limiting the traffic that enters the area. Poultry operations should have a perimeter buffer area (PBA). For backyard poultry operations, this could be a fence. In commercial operations this may be a fence or road that surrounds the facility. All entry points need to be clearly marked with “Do Not Enter” signs. In a study by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) evaluating factors associated with introduction of HPAI in layer farms in the US, the presence of a gate was found to be protective against the introduction of the virus. Gates with signage may encourage people to follow biosecurity protocols.

Inside the PBA, a line of separation (LOS) needs to be established. The LOS isolates the birds from possible sources of infections. The LOS is usually the walls of the poultry building plus the entry point. No person should cross this line without following proper biosecurity protocols. Producers should provide visitors with clean coveralls and disposable shoe covers. Visitors should wash their hands before and after visiting the facility. All visitors should dip their shoes in a disinfectant solution when entering and exiting the facility. Also, no other animals, wild or domestic should cross the LOS.

Sanitation is one of the most important parts of a biosecurity plan. All equipment, feeders, waterers, and buildings need to be cleaned and disinfected regularly. First, all fecal material and dirt should be physically removed. Next, disinfectants must be applied and allowed sufficient contact time to work properly. Foot baths need to be properly maintained. The property outside the poultry house should be kept mowed and cleaned. Failure to keep the grass cut and/or to promptly clean up feed spills is associated with HPAI.

Poultry producers must also practice good animal husbandry. Flocks need to be observed several times per day. Producers need to collect and dispose of dead birds frequently. Producer should know the clinical signs of a sick bird. Any unusual increases in sick or dead birds should be reported to proper authorities. Backyard producers have several options. They can contact their veterinarian or Oklahoma State University County Extension office. They can also contact the Oklahoma State Veterinarian at 405-522-6141.

The National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) has guidelines for a biosecurity protocol. Commercial and backyard poultry producers should examine the NPIP 14 standards of the biosecurity protocol. Any areas that do not meet the standards need to be addressed. The NPIP biosecurity audit form can be found at http://www.poultryimprovement.org/documents/AuditForm-2018BiosecurityPrinciples.pdf. Additional sources for backyard poultry producers can be found at the USDA Defend the Flock website at healthybirds.aphis.usda.gov, Protect Your Poultry From Avian Influenza at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/publications/animal_health/bro-protect-poultry-from-ai.pdf or Oklahoma State University fact sheet Small Flock Biosecurity for Prevention of Avian Influenza ANSI-8301.

Avian Influenza is a major threat to the US and Oklahoma poultry industry. It is the responsibility of all commercial and backyard poultry producers to do everything in their power to protect this industry.

Reference

Swayne, D.E. and Halvorson, D.A. 2003 Influenza. In Y. M. Saif (ed.). Diseases of Poultry, 11th ed. Iowa State Press: Ames, Iowa, 135-160.

Green, A. L., Branan, M., Fields, V. L., Patyk, K., Kolar, S. K., Beam, A., Marshall, K., McGuigan, R., Vuolo, M., Freifeld, A., Torchetti, M. K., Lantz, K., & Delgado, A. H. (2023). Investigation of risk factors for introduction of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus onto table egg farms in the United States,

2022: a case-control study. Frontiers in veterinary science, 10, 1229008.

-

Country Lifestyle7 years ago

Country Lifestyle7 years agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Outdoors6 years ago

Outdoors6 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Country Lifestyle2 years ago

Country Lifestyle2 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Farm & Ranch5 years ago

Farm & Ranch5 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine6 years ago

Equine6 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Country Lifestyle1 year ago

Country Lifestyle1 year agoSay Yes!