Country Lifestyle

Where the Paved Road Ends: Summer, Unplugged

By Beth Watkins

When we were kids, our most anticipated time of the year was summer. Summer break was meant to be a time to let our brains have a vacation from our studies, a time for Dick and Jane to run and play, barefoot outside with Spot.

I’m pretty sure our summer breaks, here in Oklahoma, were scheduled around the heat indices. We started school after Labor Day, when the temperatures began cooling off, and we got out of school in May, when the temperatures began heating up.

Our schools did not have any air conditioning. Can you imagine today’s little tykes, Braxlee and Rivers having to go to school without any air conditioning?

My husband, G.W., remembered helping in the hay fields when he was 10 years old. He was in charge of bringing water and tools out to the guys working in the hay meadow. He wasn’t big enough to push the starter button Back then, it was in the floorboard of the truck.

With the truck in gear, he would get down to push in the starter, and then he would jump back up in the seat to steer it out to the pasture. He played out of the way and stayed near the truck listening for his daddy to whistle for him to come out to them.

He entertained himself without an iPad or cell phone. Can you imagine today’s kids entertaining themselves while keeping an ear open for instruction in the hot Oklahoma sun without sunscreen?

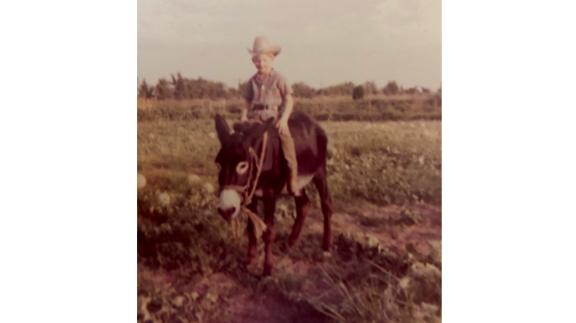

Before he was old enough to help in the hayfield, he hung around the house with his mom. He was around the age of five when the neighbors brought him a Ginny. As the stock trailer was backing in, the little cowboy, with gun and holster on his hips, was standing off to the side with his daddy, and the donkey began braying. With raw excitement he squealed, “Do you hear my horse, Daddy?” That summer, the little cowboy and his horse had many adventures.

One special activity was prospecting for gold. G.W. would lead his “horse” to the front porch where he could get on her, then ride out to the garden where he would pick the ripe cantaloupe or as little George would call them, “gold nuggets.”

One day his momma was at the kitchen window watching her baby boy ride his “horse.” When they were approaching the gate, the tiny cowboy hollered, “Whoa,” but the stubborn Ginny hesitated to respond to the order. When she finally did, G.W. went flying forward and hit the ground.

He picked himself up, dusted himself off, put his little cowboy hat back on his head, walked straight up to the culprit, grabbed her halter and punched her square in the nose and said, “I said woah, you son of a ‘biscuit.’”

Read more in the June issue!

Country Lifestyle

July 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

Riding Bulls to Raising Kids

Riding Bulls to Raising Kids

By Laci Jones

With a career as a professional bull rider that spanned more than 15 years, J.W. Hart was the 1994 Professional Bull Riders Rookie of the Year, 2002 PBR World Champion and later started the J.W. Hart Challenge that takes place each year in Decatur, Texas. However, these days Hart enjoys spending time with his family and raising cattle on the 240-acre ranch in Overbrook, Okla.

“J.W.’s bull riding career is one thing, our marriage is one thing and our kids are one thing, but the connector has been God,” said J.W. Hart’s wife, LeAnn Hart.

The bull rider was born in Marietta, Okla., in March 1975, with rodeo in his veins. His father rode bulls before Hart was born and shortly after. His mother barrel raced, later becoming a secretary.

Hart tried his hand at calf-roping, barrel racing and goat tying in junior rodeos, but he found his passion in bull riding. Both Hart and his little brother learned how to bull ride from their father from the first time they got on calves.

“My mom and dad would say when I was a kid, ‘I swear to God if somebody broke that kid’s head open it’d be nothing but bucking bulls coming out of there,’” he laughed.

Hart was an athlete in the arena as well as on the field. The football coach later told Hart he needed to choose between the two sports. After choosing rodeo as his primary sport, Hart continued to hone his skill as a bull rider.

He idolized bull riders including Donnie Gaye and Lane Frost. In 1986, the young bull rider had the opportunity to practice with Frost, who became the National Finals Rodeo World Champion Bull Rider the following year.

“It was pretty cool to practice the same day that Lane Frost was,” Hart recalled. “He was my hero. I looked up to him as an idol. You didn’t know what he would grow into, even after his death. He’s just bigger than life.”

Frost had an impact on the 11-year-old, giving him occasional advice and sending him hand-me-down shirts. The shirts were given away, and Hart said he would give anything to have those shirts back.

“What I remember most is the fact, that when I broke it down in later years, [Lane Frost] was telling me really the same thing that my daddy was telling me that I didn’t believe,” he added. “But when your hero, or your idol, tells you, well, then, it’s just the gospel.”

Hart knew at a young age he wanted to compete professionally. The PBR was not formed at the time, so he dreamed of being of competing in the National Finals Rodeo and become a world champion bull rider.

“I did know from a really, really young age that what I wanted to be is a bull rider,” he added. “I never had dreams or aspirations to be an astronaut, or a doctor, or a scientist.”

He was too young to remember the first time he rode a bull, but the first time he rode a full-grown bull was memorable for Hart. The 12-year-old bull rider had teeth shoved underneath his eye socket and broke his upper jaw. However, he was resilient and kept improving as a bull rider.

By the time he was 18 years old, he was making a name for himself. When the PBR first formed, the qualifying system used today did not exist. Instead, the best in the world as well as new riders were invited, including Hart.

“They didn’t have to chase me very far,” Hart joked. “All they had to do is look out the window, and I was standing there. That’s how I got my start. I got an invite, made the list a few times right off and they let me keep coming back.”

One of his first rodeos in the PBR was in the old Texas Stadium. He was an alternate who found out he was going to compete the week before. Hart met the buzzer when he rode Voodoo in the first round, attributing the successful ride to the muddy arena.

“Nobody ever really rode that bull ever, and I rode him in the mud,” Hart explained. “Probably the mud is why I rode him. He didn’t have quite the day he was capable of.”

The former professional bull rider said the rides throughout his career have become a blur, but one of his more memorable rides was at the second PBR World Finals in 1995 when he rode a bull named Erkel.

“I remember that one really well,” he explained. “It probably wasn’t my best ride ever. I know it wasn’t the highest score ride ever because it was only 89 points, but it was probably one of my favorite rides.”

He said it was one of his favorites because he discussed the upcoming ride with friend, Cody Lambert. When Hart asked Lambert what he thought would be a good way to ride Erkel, he replied, “When the gate opens, just start spurring.”

When the gate opened in 1995, Hart immediately started spurring. Looking back, Hart said he rode him that way to say to Lambert, “You told me what to do; I can do it.”

Another memorable ride occurred two years later at the Calgary Stampede, where he rode Kodiak. Again, Hart said it was not his highest scoring ride, but only one other bull rider had ever ridden him.

“One of the greatest bull riders of all time, Troy Dunn, was the only guy at the time to ever make the whistle on that bull. I think that was one of my best rides, not just because it was for the $50,000 bonus that day. It was at my favorite rodeo of all time, and we’d all just come together. That was one of the most memorable moments.”

Toward the end of his career as a bull rider, Hart was presented the opportunity to get into broadcast. After he was finished riding for the day, the network was looking for a different perspective from one of the riders, he explained. The bull rider filled in and talked with the commentators about his views on the championship round. The following year, he was offered a job as a broadcaster for PBR.

“I had enough common sense about me to know that my career was in the later years,” he added. “I wasn’t feeling good anymore, and my body was starting to not react the way I needed it to.

“Not that I probably couldn’t have went another year and fought through it, but I thought if I went on trying that I might miss the window of my next career, next opportunity. I was starting a family, and had somebody else to think about besides myself, so it was kind of a natural progression to do something different.”

More than 10 years after his slight career change, Hart is still broadcasting along with other former bull riders including Justin McBride and Ty Murray. Being a former bull rider and a broadcaster, Hart said bull riding has evolved in three major aspects including the bulls.

“The best bull then rivals the best bull today, there’s no doubt,” he began. “The very best ones don’t get no better. From middle of the road to the bottom, we got on the best bulls in the world then. But they’re nothing, absolutely nothing compared to the bulls that are going today.”

The second major change he has seen is the award money. Hart won $102,000 in his rookie year in 1994, which was a considerable amount at the time, he added. The 2016 PBR World Champion, Cooper Davis, won nearly $1.5 million.

Finally, Hart said bull riding is more mainstream than in ‘90s. Hart said bull riding was once considered a niche sport, almost a sideshow to other sports.

“Now, our guys are on the covers of Men’s Sports Fitness, on the front of the New York Times, and we’re getting on national television, and not just the CMT or TNN back when we had to pay for the time. We’re on CBS Sports and CBS on a weekly basis,” he explained.

Hart also decided to focus on his bucking bull program he started in 1995. He started the program toward the beginning of his career because he knew his career as a bull rider would not last forever, but he wanted to still be involved in the industry. Today, he has 55 head of cows that will be bred this year along with approximately 60 head of bulls. All cattle at the ranch are for sale, he added.

“Our cows make bucking bulls for bull ridings,” he stated. “We take care of cows that make calves to go to bull ridings. When we work cattle, we’re working bucking bulls.”

In January of 2015, he began preparing to make a comeback in the arena for Unfinished Business, where eight former PBR bull riders came out of retirement to compete in Decatur, Texas.

“I wanted to make a point because my son had been asking me, ‘Dad, I want to see you ride a bull,’” he explained. “I told him, ‘I don’t ride bulls no more.’ I showed him [videos] on YouTube, and he didn’t think that was fit. He wanted to see me ride a bull.”

Hart was planning on getting on a bull in the practice bull so his son Wacey could see him, when he got an offer for Unfinished Business. He said it was an opportunity to “kill two birds with one stone.” Wacey could see him ride while also making his last stand as a bull rider.

“I figured if I was going to do it, it was time to show my son that if you want to do something, you’ve got to put out the effort,” he added.

To set an example for his children, Hart trained for four months with a personal trainer and was on a strict diet. He said he was in the best physical shape of his career when he and Chris Shivers won Unfinished Business, splitting the $160,000 payout.

When asked if Wacey was satisfied with seeing him ride, Hart replied, “I think so. He better be because I ain’t doing it again.”

Hart’s wife, LeAnn supported him throughout his career as a bull rider, broadcaster and ranch owner. He first met his wife of nearly 12 years through mutual friends, each dating different people. LeAnn joked that her first thought of Hart was “he was a butt.”

“We were very competitive,” LeAnn added. “We had a crawfish eating contest, and I beat him. He’ll say it different, but I did.”

They did not cross paths for a couple of years until a bull riding in Tampa, Florida, Hart explained. The two started dating and were married in 2005. The Harts started trying to have kids soon after, but were unable to carry a baby to full-term.

“We have 11 babies in heaven,” LeAnn explained. “So, we got a little football team up there.”

They prayed over their options and explored adoption. In 2008, they were chosen to be parents and Wacey Hart was born in March 2009. A year later, Makayla Hart was born and the Harts adopted her.

Two years ago in September, the Harts got a call about a two-year-old local baby who needed a home. It took nine months to finalize the adoption of Elsie Hart. The Harts have been able to keep an open adoption with each of the parents they have adopted from.

They have also been foster parents for the last eight years, recently taking a break. A year ago, they took in a local teenage boy. LeAnn said they have not adopted him and he is not a foster child, but instead a local boy who needed a family.

As for the future, Hart joked that he would like to “make a gazillion dollars, retire and do what I want every day.” In reality, the former professional bull rider said he lives the life he has always dreamed. The Harts said God has blessed them with healthy kids, a beautiful home on the ranch and cattle.

“I’d like to say that next week I might change my mind and want to start surfing, but I don’t see that happening,” he added. “It’s bull riding. It’s always been bull riding.”

This article was originally published in the July 2017 issue of OKFR!

Country Lifestyle

May 2017 Profile: Terry Stuart Forst

By Laci Jones

Fire engulfed thousands of acres of land across Colorado, Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma in early March. Ranchers risked everything to try to save their animals as their livelihoods went up in flames.

“It’s devastating,” Forst explained. “It’s us. I know it is hard for people who don’t make their living off the cows and grass to totally understand. For those of us who do, we are right there with them.”

The recent devastation hit home for Forst as she has spent more than 40 years in the industry, nurturing the land her ancestors bestowed to her.

(Courtesy of Stuart Ranch)

History of Stuart Ranch

For nearly 150 years, Stuart Ranch has faced droughts, flooding, tornadoes and have persevered. The ranch was founded by Forst’s great-great grandfather, Robert Clay Freeny. In 1838, Robert Freeny traveled to Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory and married Sarah “Sallie” Ellis.

The couple, along with their 13-year-old son, Robert “Clay” Freeny, Jr., settled 14 miles west of Atoka in Boggy Depot in 1868. During that time, the family raised cotton, oats and corn.

“Cotton was huge back in that area across the Highway 70 corridor,” Forst said. “I had always been told they traded a lot of horses and mules to the U.S. Army.”

Before her death in 1868, Sarah Ellis Freeny gave birth to 12 children. That same year, Robert Freeny moved the family to Caddo before relocating north of what was once known as the Redlands in Blue County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. Clay Freeny took over the operation after Robert Freeny died in 1878.

Clay Freeny, also known as Judge Freeny, continued to farm as well as raise cattle, horses and mules. He was named the County and Probate Judge of Blue County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. After the death of his wife, Mary Beck in 1894, he married Josephene Baxter.

At the turn of the century, Carrie “Ida” Freeny was born to Judge Freeny and Baxter. She attended the Tuskahoma Choctaw School for Girls and later married Robert Terry Stuart, the son of a cattle rancher, in 1931.

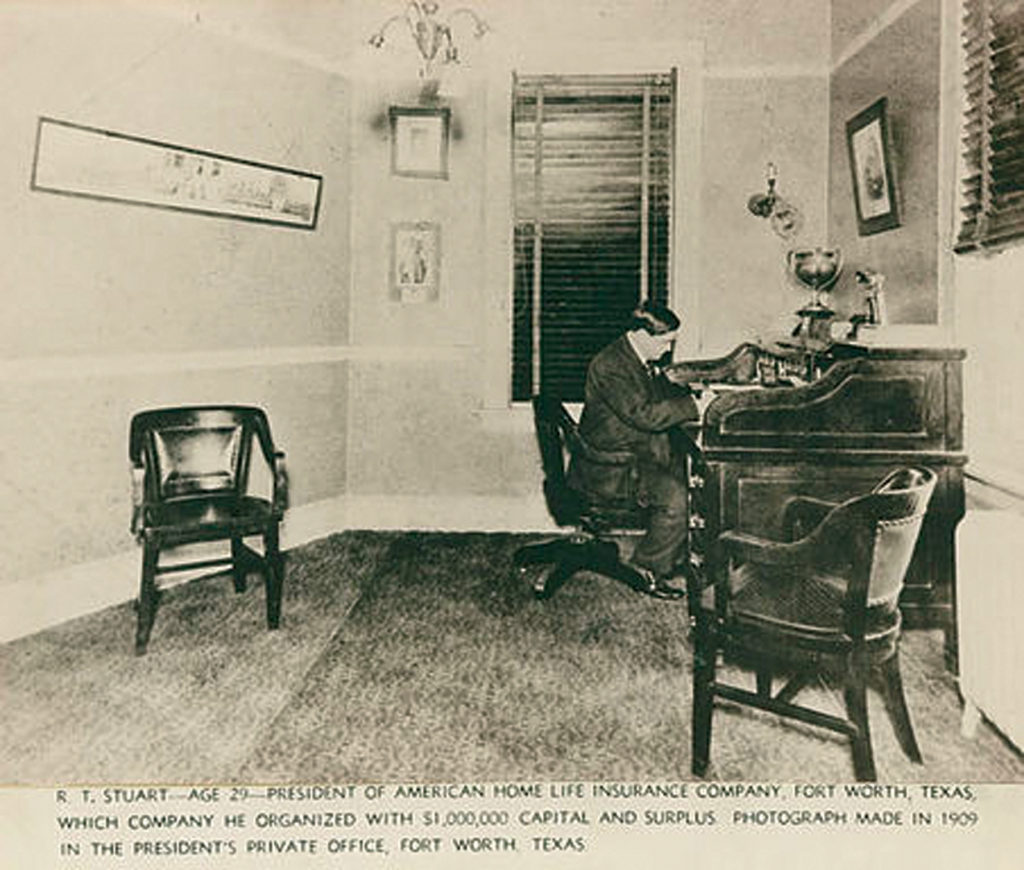

After working with the Pacific Mutual Insurance Company and the American Home Life Insurance Company in Fort Worth, R.T. Stuart purchased the Mid-Continent Insurance Company in Muskogee, Okla., in 1916. He relocated the company to Oklahoma City, where he and Ida Freeny Stuart resided and operated the ranch.

R.T. Stuart focused on improving the cattle operation, introducing Hereford cattle to the ranch. Two years after they were married, Robert Terry “Bob” Stuart, Jr., was born. Bob Stuart later took over the operation in 1950, where he focused on improving the horse operation by purchasing the ranch’s first Quarter Horse in the ‘40s.

Bob Stuart purchased a stallion named Big Shot Dun from 3-D Stock Farm, a part of the Waggoner Ranch, in 1949. Progeny bred to Son O Leo, purchased in 1961, proved to be a successful match.

The Terry Stuart Forst Era

Forst was born in Oklahoma City in 1954. Forst inherited her father’s passion for horses, riding every chance she could get. While Bob Stuart was supportive of his daughter’s passion for showing horses, he pushed her to find her own path. Forst showed in the American Quarter Horse Association Youth classes.

“I struggled, fumbled and showed up,” Forst explained. “I think my friends thought I was great because I was the ‘class filler.’ I wasn’t ever going to beat anybody, which was fine.”

Forst continued to show horses in the AQHA shows after she turned 18, enrolling at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater, Okla., bringing horses along. Forst pursued a bachelor’s degree in animal science.

The university helped Forst develop relationships that have lasted for decades. After graduating in 1976, she returned to the ranch and helped her father with the horse program. The OSU alumna said she had the intention of returning to the ranch after graduation. Her goal was to prepare herself for her role on the ranch.

“That is all I ever wanted,” she added. “I never wanted to go anywhere else, but I wanted to do a good job for him. That was important to me.”

When asked what her father taught her, she laughed and said her dad “threw me to the wolves,” but in a good way.

“I learned a lot on my own, but I learned things because of either questions he would ask or questions I would have about the way he was doing things,” the rancher said.

After returning to the ranch, the father-daughter duo enhanced the horse program, later earning the AQHA Best of Remuda award in 1995. Due to conflicting visions for the ranch, Forst left Stuart Ranch in 1989 and worked for a real estate broker.

“I really wasn’t sure if I would go back to the ranch, but I wanted to stay in agriculture and in this business.”

With two young boys to raise, Forst was accepted in the Texas Christian University’s ranch management program. The program was a stepping stone for Forst. She had her real estate license and wanted to become a rural appraiser.

Forst was preparing to start her own business when Bob Stuart called and asked her to take a look at a piece of property. The property was one of the few continuous operations in Oklahoma, where the land is not separated by roads or fences, which peaked Bob Stuart’s interest. She visited the property and prepared a management plan. When she presented the plan to him, he asked her to execute the plan.

“We made a deal where I had to get him profitable within a certain period of time, or I was going to leave,” Forst explained. “I had a job and if I couldn’t do it, then I wasn’t the one he needed to do it.”

They purchased the 11,000 acres east of Waurika, Okla., in 1992. She hired her TCU colleague, Jay Adcock to help put the ranch together as far as cattle and fencing. While it was a monumental task, Forst followed the management plan and succeeded while she and her family were still living in Caddo, Okla., at the time.

Soon after, Forst moved the family to Waurika, Okla., and took over the operation as ranch manager. The ranch manager said when she took over, she had goals for the ranch and a deadline to reach them.

Preparing for the Worst

She continued to learn and enrolled in courses at Kansas State University, read literature and exposed herself to new ideas. To this day, the ranch manager considers herself “a sponge” when it comes to range management. Forst has worked with her crew to understand more about grazing within the last five years.

“There’s always been a limiting factor—water,” Forst explained. “There is no groundwater here, only surface water. When you are surface water dependent, it changes the dynamic of a lot of things.”

While the ranch always prepares for the worst, the drought of 2011 was monumental. From one extreme to another, she said 2014 and 2015 saw massive amounts of rain. The ranch has faced weather challenges throughout the past few years, but Forst said those are situations they must manage.

Allocating money each year toward water development is an integral part of the budget because they understand how critical it is. This year, she plans to increase distribution to become more efficient. Forst has worked with her crew in implementing these changes.

“The crew has been really receptive,” she said. “You can’t do things by yourself with people who are better than you at a lot of things and strive to be the best they can be. I’ve got a crew like that.”

Future Generations

“A family operation is one of the most difficult operations to be a part of, but it is also the most rewarding,” Forst explained. “To know you are able to carry on a legacy that started 150 years ago, and know that you have been entrusted to make sure you hold it together, I don’t take that lightly.”

While the responsibility can be daunting at times, Forst has tried to prepare the next generation to take the reins. The mother of two has turned many sections of the operation over to the next generation, her sons Robert and Clay Forst.

“I think it is more advantageous for them to make mistakes while I can help them through it,” she added. “They have done a wonderful job and have worked hard their whole lives.”

Both Robert and Clay understand learning is an ongoing process. Forst said ranching will only continue to get more difficult as society finds themselves further removed from agriculture. The rancher said a rancher needs to be resilient, dedicated and have faith to be successful.

“I think you have to have a tremendous faith in God,” the rancher stated. “You see that evident every day. We are just stewards.”

Stuart Ranch by the Numbers

Knowing if the ranch does not move forward, it will move backwards, Forst has made it her mission to evolve. Today, the ranch consists of 45,000 acres of land.

“Our pastures are in good shape,” Forst explained. “This year’s prescribed burn was the best in 30 years.”

The ranch incorporated a no-till method in their operation. Thinking long-term, Forst said she hopes to increase soil fertility and cease using fertilizer 15 years from now.

Forst’s grandfather, R.T. Stuart, started with Herefords, but today they have Hereford and Angus cattle. The black baldie is their super cow—making up about 60 percent of the herd. While the cow herd number is down to 1,600 head, they plan to build their numbers this year.

“A goal for us is to be better next year than we were this year,” she added. “We sold heifers when the market was good, so now is when we want to start building the herd more than anything.”

Selling many of their replacement heifers has helped the rancher focus on improving herd genetics by developing an efficient and productive cow. Along with their cow/calf herd, the ranch also specializes in stocker cattle. The steers do well in the feedlot, according to Forst.

Stuart Ranch has also expanded on their horse operation with approximately 150 head of horses. Each day, they train, promote and show their quarter horses. Forst said they are looking forward to the 2017 Snaffle Bit Futurity, which will take place in Ft. Worth, Texas, this October.

“Because of the proximity, people can come and look at our horses,” she added. “We wanted to be in a good position to have horses for sale.”

Forst is considering opening a small horse rehabilitation facility on the ranch in the future as well. She saw a need for the facility in the area for other horse owners to use. She hoped new additions to the ranch will enhance their horse operation.

“We have diversified and evolved from our roots and traditions,” Forst explained. “Those things are important to us and we highly value our legacy and what we have been entrusted with and hope to continue in a profitable fashion.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Country Lifestyle

Hardy Murphy Coliseum

By Judy Wade

Many people consider the Hardy Murphy Coliseum in Ardmore an equine facility only. It does, indeed, host a myriad of horse-related activities each year, but also a variety of non-horse events.

The first building was constructed in the mid-1930s by the Works Progress Administration. The arena was 270 feet by 130 feet, and for the first 10 years was a roofless stadium known as the Municipal Exhibition Building. During a rodeo, a bull jumped the fence, charged uphill through scattering spectators, and did a swan dive into the parking lot, where it had to be euthanized.

During the late 1940s a roof was added and a better fence separated animals and spectators. It hosted a livestock show, professional rodeos, the Ringling Brothers Circus and other civic events.

In the early 1960s, the coliseum was renamed for Ardmore native, Hardy Murphy. Murphy was a rodeo performer and Wild West Show star whose show business career spanned three decades.

It could be said that horses ran in Murphy’s blood. Born in 1903, the grandson of a Texas horse trader, he developed his love for horses into a career of international acclaim as a horse trainer and rodeo showman. His horses, Buck and Silver Cloud, were a big part of his show, especially well-known for pantomimes of famous scenes by western artists and sculptors, even gracing the cover of The New Yorker in 1944.

Murphy loved to perform and demonstrate his skills whether it be for the Royal Court in London, spectators at Madison Square Garden or children around the world. His favorite charity work was at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, performing for seriously or terminally ill children.

Murphy and Buck were top billing in Col. W.T. Johnson’s rodeo in Madison Square Garden for 10 years. After retiring from the circuit, he returned to Ardmore in 1943 where he began a second career as realtor, promoter, volunteer, and part-time performer for charities and civic events. He was frequently referred to as “Southern Oklahoma’s Goodwill Ambassador.”

Buck was retired in 1953 in a nationally televised show during the Fort Worth International Stock Show. Both Buck and Silver Cloud are buried on the coliseum’s grounds. Ardmore school closed for Buck’s funeral when he died at age 34, and Gene Autry was among the 10,000 admirers of Murphy and his horses who attended the ceremony.

Murphy died in 1961 at age 58.

The Hardy Murphy Coliseum fell into a period of neglect and disrepair during the early 1970s. In the mid 1980’s a group of concerned citizens organized into the Hardy Murphy Coliseum Trust and Authority and began renovating the building.

Today the sprawling complex covers 30 acres, according to Jeff Storms, manager of the Hardy Murphy Coliseum. The renovated coliseum now seats 4,000, is climate controlled, has an enclosed announcer’s booth, a fully-equipped kitchen, show office, 18,000 square feet available for trade shows, restrooms, and showers.

Two additional covered arenas, a new building, and multiple stall barns make the Hardy Murphy an ideal place for events.

“We already have the usability and functionality to compete with moderate-sized facilities around the state,” Storms said, “but, we are continually striving to make improvements.”

In addition to the graves of Buck and Silver Cloud, a historic steam locomotive, engine number 1108 sits on the coliseum grounds, commemorating a tragic event in Ardmore’s history in 1915. A railroad worker was repairing a gasoline tanker car near East Main Street when a spark ignited an explosion. Fifty people were killed, many more injured, and much of the downtown area was destroyed. A call for help went out, and engine 1108 came from Gainesville, Texas with a full head of steam, bringing life-saving medical personnel, making the 45-mile stretch of rail in record time.

A life-size buffalo sculpture also sits at the entrance. More than 100,000 people visited Hardy Murphy Coliseum last year.

“A study showed that in 2013 the coliseum events generated a $5.1 million impact on Ardmore. In 2014 that figure rose to $6.3 million; and through October of this year, it has risen to over $7 million,” Storms said.

Events are held 48 weeks of the year spanning anywhere from one to 10 days.

There is truly something for everyone to be had at some time during the year at Hardy Murphy Coliseum at 600 Lake Murray Drive.

For more information, visit hardymurphycoliseum.com, or call Jeff Storms at 580-223-2541.

This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Country Lifestyle1 day ago

Country Lifestyle1 day agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Country Lifestyle3 years ago

Country Lifestyle3 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Outdoors7 years ago

Outdoors7 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Farm & Ranch6 years ago

Farm & Ranch6 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Outdoors3 years ago

Outdoors3 years agoSuzy Landess: Conservation carries history into the future