Farm & Ranch

Leading By Example

Jimmy Emmons

Jimmy Emmons admits some of his ideas about conservation techniques have been met with a bit of skepticism over the years, and that’s why the Leedey, Okla., farmer, chooses to lead by example. Instead of pushing others to try out his techniques, he shares his findings and results with anyone who wants to learn. His desire to be a steward of the land, and his dedication to teaching, has led Jimmy to hold several major positions in agriculture over the years, from serving as President of the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts, to his current title of Southern Plains Coordinator for USDA, FPAC.

Emmons and his wife Ginger, along with longtime employee Karson Liebold, farm and ranch on several thousand acres in Dewey County. The land has been in the Emmons family since 1926, when his grandfather, Marvin Curtis Emmons, moved to the area. A major event just a few years after the Emmons settled in the area that would set the course for generations of conservation efforts.

“My grandparents started farming on the South Canadian River, and in 1934, the Hammon Flood happened. It rained 14 inches in one night, and killed several people,” Jimmy said.

Prior to the torrential rains, Jimmy’s grandfather had started a small ditch across the farm to take water from one area to another. “That night it burst that ditch out to a creek that was 20 feet deep and 30 feet wide,” Jimmy shared. All the topsoil had washed off into the river. “He preached really hard about conservation, and that really instilled in me that everything we do on the land has a consequence. Conservation has been a passion of mine for several years.”

Karson, who has worked for Jimmy and Ginger for more than 12 years, has enjoyed learning about the affects of conservation practices on the soil. “It’s amazing. I’ve gotten to watch the soil change. It’s funny, because at my previous job, it was all about wheat. I remember when I first started here, I was looking at a field and thought to myself, ‘Look at all those weeds!’” He laughed, and added, “It was canola. I had no idea of the things that could be grown out here. We prove every day that you can have a lot of diversity, and obviously having that diversity benefits your soil.”

Maximizing Resources

The Hammon Flood was an outlier; water is a precious commodity because rain is so scarce. Jimmy knew he needed to maximize his natural resources.

As with most farmers, the Emmons originally tilled the soil, but that changed in the mid-1990s. “I can hardly stand to see tilled ground now, because I know the damage it does to the soil. Tillage is just like a wildfire or a tornado to the soil. It’s devastating,” he said. “I grew up with that and thought we were doing what we were supposed to do, but now I know better.”

Over the years, Jimmy has learned more conservation practices that might benefit his land, utilizing crop rotation, cover crops, and planned grazing management. Ginger, whose main focus is the cattle, shared, “Once we got into the cover crops, the grazing has been fantastic for the cattle and the land. We can run our cow/calf pairs or our weaned calves on it.”

One method of grazing the Emmons have implemented is high-density grazing. They divide a field into sections, which are approximately 20-acre plots. Then, with an electric fence, they graze the area hard for a couple days. Once the area has been grazed, they move to the next parcel. “You just keep moving it. If you have had some rain, by the time you’re done with the last parcel you can move back to the first,” she said. “All that manure is contained, so that’s great for the soil. The cows do well with it, and it’s amazing how well it works all the way around.”

Jimmy noted, “We started planting cover crops right after we harvest our cash crops. We started grazing those crops to continue to improve the soil health, and it has grown from there, and greatly improved the function of the soil.”

The idea to use cover crops came when Jimmy heard a producer from Indiana speak about the practice at a national conservation meeting. “He showed photos and figures of his plots. He wasn’t buying any fertilizer for his cash crop, and he not only improved production, he also lowered the cost,” Jimmy said. “I thought to myself, ‘If he can do it there, why can’t I do it here?’”

The use of cover crops in western Oklahoma was somewhat controversial due to the scarcity of water, and Jimmy knew he needed to recruit some help. “The big argument early on, and the reason I asked the NRCS for help, was that we can hardly grow crops out here. How can we grow continuously?” He added, “We quickly started learning that the evaporation rate was a lot greater in the summertime than what a cover crop would use. We figured out we were water ahead every time.”

Jimmy was energized by the early success of the tests. “When you start retaining what rainfall you have, that’s the key. You have to get it in the soil,” he said. “Although I was excited, I was still a bit skeptical at first. I bought my testers and we put moisture probes in the ground so we could track the water that was in the soil and see how fast it left.”

It was only a few years ago that the Emmons put an irrigation system on some of the farmland. At first, the ground could barely hold a half-inch of water before running off. A recent test showed infiltration depths of six inches! “You know, we’re working on a project right now with the Conservation Commission and the NRCS about infiltration rates. We’re seeing how much water we can take in and at what rate, and then we’re seeing how it is going through the profile,” he said. “I think it’s especially important for producers to understand the science of it. I believe it is something we have missed as a farming community; we’ve always been worried about how much it rains, but we haven’t been as concerned with how much we’ve had run off. I think we need to focus on infiltration.”

He admits that it all comes down to the bottom line. “You know, we are really concerned about inputs nowadays, but what we found out is if you have the biology really active in the soil, you don’t need near as much synthetic fertilizer. Every dollar you don’t spend is more dollars you have,” he said. “These days, we’re not so worried about the high yield as we are the profit potential. It’s been very good.”

Giving Back

It was only a few years ago that Jimmy was visiting with Sarah Blaney, Executive Director of the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts, and Trey Lam, Executive Director of the Oklahoma Conservation Commission. The three were discussing cover crops. “Trey mentioned putting vegetables out there to see how they would work as cover crops. That started the conversation, and then it grew to, if this is going to work, what if we partnered with the regional food banks and donated the vegetables,” he recalled.

What started as a small idea has grown to include more than 30 gardens across the United States. “We have several across Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, and now we have some in California, too,” he said.

During good rain years, the yields have been abundant. “During those years, you can pick a half pickup load of vegetables, from squash, peas, okra, and more. One year we could pick close to 1,000 pounds in a day out of only a few acres,” Jimmy shared. “Some days were even more. This year we won’t get much, because we had so little rain, as well as the 100-degree days and the big wind. There are other gardens in the state that are producing well though.”

Produce from the crops go to nearby foodbanks in Woodward, Vici, and Taloga.

Volunteers are always available to help harvest the crops. Along with the foodbank volunteers, church groups, local FFA chapters, and more will come out to help. “It’s a very good project, and one we’re proud of. Not only do we help get fresh vegetables to people who need it, it also helps urban people interact with ag and learn more about where their food comes from.”

Sharing the Knowledge

Over the years Jimmy has become known for his conservation practices and their success. Soon, he began getting tapped for speaking engagements. He shares what he’s learned about soil health at several workshops. “It’s really fascinating to me what we can do with our soil. One of the most rewarding things is when someone you’re sharing with gets excited, and wants to try it, too,” he said.

Along with the lectures he has done all over the country – during one period he visited nearly 30 states in three years – the Emmons have hosted legions of fellow farmers from around the globe at their home in Leedey during field days. “Two years ago, we had a busload of Australians come. We’ve also hosted Canadians and Europeans. We’ve been very blessed with the people who want to come to our place and see what we’re doing,” he said.

Setting an Example

Ginger is incredibly proud of Jimmy’s success, although she admits she was a bit skeptical at first. “I wasn’t very supportive at first. It wasn’t until we started doing the grazing and I saw what that could do, and then I was on board. But now, I’ve learned more about it, seen what it can do, and gone to enough conferences with him. I do get it now and it’s the greatest thing we’ve ever done,” she shared.

Ginger added, “We both just have high school degrees, and he’s just moved up through the ranks and has a really good job now. I’m amazed when I listen to him speak and realize how much he’s learned. I’m very proud of him.”

The Emmons, who were high school sweethearts, have been together more than 38 years. Karson, being so close to the family, is regularly mis-identified as Jimmy and Ginger’s son; but that’s something he’s ok with. He’ll be getting married himself in October, and shared, “I’ve watched how Jimmy and Ginger love each other. I told Jimmy the other day, that if my marriage is the way theirs is, it will be perfect.”

Looking Ahead

Jimmy has a vision for the future; one that sets the farm up for success for the long term. He hopes to leave it for his grandson one day. “My grandfather did the best he could with the tools and knowledge he had to manage our family’s land. I am trying to continue that legacy by using what we now know are the best practices for improving the health of our soils. My goal is that my grandson, Owen, and his children will be able to farm this land for another 100 years, if they choose. That is only possible if Ginger and I do our part to take care of the natural resources,” said Emmons.

He would like to eventually start producing organic crops, and because of the conservation practices he’s implemented, the use of synthetic fertilizers on the Emmons farm has been reduced by 80 percent and chemicals by 75 percent.

Jimmy also has plans for his cattle. “We would like to start our own label for regenerative beef, meaning we have healthy soil which produces healthy plants and that becomes healthy beef that will create healthy bodies,” he shared. “The thing about our beef is they never graze on one plant. We believe in diversity in crops, forage for grazing and native ranges. We all like a buffet where you can select what you like to eat so why not treat your animals the same way.”

This article was originally published in the September 2020 issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Lice in Cattle

Barry Whitworth, DVM, MPH | Senior Extension Specialist

Department of Animal & Food Sciences | Freguson College of Agriculture | Oklahoma State University

Cattle lice cost Oklahoma cattlemen millions of dollars each year in decreased weight gains and reduced milk production. If cattle producers have not treated their cattle for lice this fall, they need to consider what type of lice control to initiate. This is especially true for cattle producers that had problems in the previous year. Cattle producers should monitor cattle closely during the months of December, January, and February. Producers should not wait until clinical signs appear before beginning treatment.

The life cycle of the different species of cattle lice are very similar. The life cycle begins with the female louse attaching her egg to a shaft of hair. The egg will hatch as a small replica of the adult. After several molts, the adult will emerge. The cycle takes around 3 to 4 weeks to complete. These newly hatched lice will spend their entire life on the host and are host specific which means cattle cannot be infected with lice from other animals.

Small numbers of lice may be found on cattle in the summer, but high populations of lice are associated with cold weather. Since cattle tend to be in closer proximity to each other in the winter, lice can spread easily between cattle. A small percentage of cattle tend to harbor larger numbers of lice. These animals are sometimes referred to as “carrier animals”, and they may be a source for maintaining lice in the herd. As with many other diseases, stress also contributes to susceptibility and infestation.

Signs of lice infections in cattle are hair loss, unthrifty cattle, and hair on fences or other objects. If producers find these signs, they may want to check a few animals for lice. They can check for lice by parting the hair and observing the number of lice per square inch. If an animal has 1 to 5 lice per square inch, they are considered to have a low infestation. Cattle with 6 to 10 lice would be considered moderately infested. Any cattle with more than 10 lice per square inch are heavily infested.

Cattle have two types of lice. One type is the biting or chewing louse. These lice have mouth parts that are adapted to bite and chew the skin. The second type is sucking louse. These lice have mouth parts that will penetrate the skin and suck blood and other tissue fluids. It is not uncommon for cattle to be infested with more than one species of lice.

The biting or chewing louse is Bovicola (Domalinia) bovis. This type of lice feeds on hair, skin, skin exudate, and debris. Typical clinical signs with this type of louse are hair loss, skin irritation and scabs on the skin. They are found on the shoulders and back.

Four types of sucking lice can be found in the United States. The first is the “short nose” louse or Haematopinus eurysternus. This is the largest cattle louse. This louse is found on the neck, back, dewlap, and base of the tail. The second is the “long-nose” louse or Linognathus vituli. This louse is bluish in color with a long slender head. This louse is found on the dewlap, shoulders, sides of the neck, and rump. The third is the “little blue” louse or Solenoptes cappilatus. This louse is blue in color and is the smallest cattle louse. This louse is found on the dewlap, muzzle, eyes, and neck. The last is the “tail” louse or Haematopinus quadripertuses. This louse has been found in California, Florida, and other Gulf Coast States. This louse is found around the tail.

The sucking lice have the potential to cause severe anemia if the numbers are high. This can result in poor doing cattle or in extreme cases death. They also can spread infectious diseases. The long-nose louse has been found to be a mechanical vector for anaplasmosis.

Prevention of lice infestation should begin in the fall. Producers should not wait for clinical signs to appear before beginning treatment. Several products are available to control lice. Producers should read and follow the label directions. Producers should keep in mind that many of the lice control products require two administrations to control lice. Failure to do this may result in cattle having problems with lice infestations.

Some producers have complained that some products do not work. These complaints have not been verified; however, this is a good reason to consult with a veterinarian for advice on what products to use. Most treatment failures are associated with incorrect application not resistance. Proper application of Pour-On insecticides is to administer from the withers to the tailhead. Also, the proper dose is essential for good control.

Cattle producers need to consider a few other things in lice control. Since cattle in poor body condition are more prone to lice infestation, producers need to be sure that the nutritional needs of their cattle are being met. Cattle that have a history of lice infestations should be culled. Lastly, any purchased cattle need to be inspected for lice before entering the herd. If lice are found, the animals should be isolated and treated before entering the herd.

If producers would like more information on lice in cattle, they should contact their local veterinarian or Oklahoma State University County Extension Agriculture Educator. They may also want to read Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet Beef Ectoparasites VTMD-7000 at https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/beef-cattle-ectoparasites.html.

Farm & Ranch

From Plow to Plentiful: The Most Important Inventions in Agricultural History

Agriculture is the foundation of human civilization. Throughout history, the quest for more efficient and productive methods of farming has led to the invention of countless tools and technologies. These inventions have not only revolutionized agriculture but have also played a pivotal role in shaping societies and economies. In this comprehensive exploration, we will delve into some of the most important inventions related to agriculture that have had a profound and lasting impact on the way we grow and harvest food.

The Wheel and Axle: Unlocking Mobility and Productivity

The wheel and axle, one of the earliest inventions in human history, had a significant impact on agriculture. This invention, which dates back to around 3500 BC, revolutionized transportation, making it possible to move heavy loads and machinery more efficiently. In agriculture, the wheel and axle played a crucial role in the development of carts, wagons, and plows, enabling farmers to transport goods and cultivate larger areas of land.

The Plow: Cultivating the Earth’s Riches

The plow is arguably one of the most iconic agricultural inventions. Its origins trace back to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt around 3000 BC. The plow transformed agriculture by allowing farmers to dig deep furrows in the soil, turning it over and aerating it. This improved soil quality, making it more fertile and suitable for planting a wider variety of crops. The plow’s evolution from simple wooden implements to more sophisticated steel plows in the 19th century drastically increased the efficiency of farming.

Irrigation Systems: Mastering Water Management

Irrigation systems are a testament to human ingenuity in harnessing water for agriculture. The earliest known irrigation systems date back to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, around 6000 BC. These systems, which transported water from rivers to fields, allowed farmers to cultivate crops even in arid regions. Over time, irrigation methods have become increasingly sophisticated, incorporating canals, pumps, and drip irrigation systems, ensuring a consistent and controlled water supply for agriculture. Today, modern irrigation practices help feed billions of people around the world.

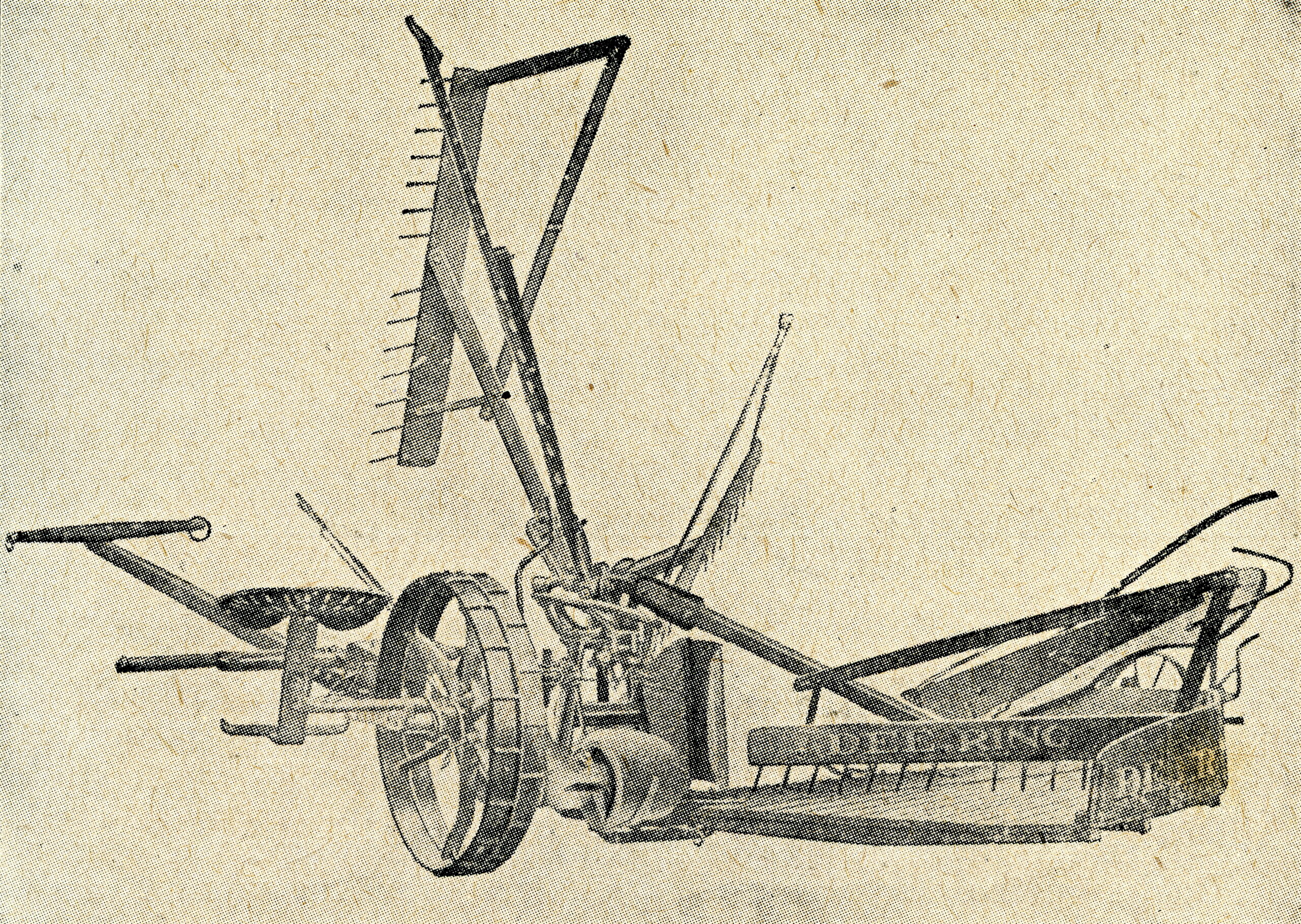

The Seed Drill: Sowing the Seeds of Precision

The seed drill, invented by Jethro Tull in the early 18th century, represented a leap forward in precision agriculture. Before its invention, seeds were sown by hand, resulting in uneven distribution and often wasteful planting practices. Tull’s seed drill, powered by horses, allowed farmers to sow seeds at a consistent depth and spacing, significantly increasing crop yields. This invention laid the groundwork for modern agricultural practices, emphasizing efficiency and precision in planting.

The Cotton Gin: Revolutionizing Textile Production

While not directly related to food production, the cotton gin, invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, had a profound impact on agriculture in the American South. This revolutionary machine automated the process of separating cotton fibers from their seeds, increasing the efficiency of cotton production by a factor of 50. The cotton gin’s success led to the widespread cultivation of cotton as a cash crop, shaping the economic landscape of the Southern United States.

The Mechanical Reaper: Harvesting the Bounty

The mechanical reaper, invented by Cyrus McCormick in the 1830s, mechanized the labor-intensive process of harvesting grain crops such as wheat. This invention featured a cutting mechanism that could efficiently harvest crops at a much faster rate than manual labor. The mechanical reaper played a pivotal role in increasing agricultural productivity during the 19th century and contributed to the expansion of agriculture in the United States.

The Steam Engine: Powering Progress

The steam engine, invented by James Watt in the late 18th century, revolutionized agriculture by providing a reliable source of power for various farming machinery. Steam engines were used to drive pumps for drainage, power threshing machines, and even locomotives for transporting agricultural goods to markets. The introduction of steam power marked a significant shift from human and animal labor to mechanical power, greatly increasing agricultural efficiency.

The Refrigerated Railcar: Expanding Food Distribution

In the late 19th century, the refrigerated railcar, often credited to Gustavus Swift, transformed the way food was transported and distributed. Before its invention, the transportation of perishable goods was a major logistical challenge. Refrigerated railcars allowed for the long-distance shipment of fresh produce, meat, and dairy products, opening up new markets and ensuring a more reliable food supply for urban populations.

Pesticides and Herbicides: Protecting Crops

The development of synthetic pesticides and herbicides in the 20th century marked a significant milestone in agriculture. These chemical compounds, such as DDT and glyphosate, helped farmers combat pests and weeds that threatened their crops. While these chemicals have played a vital role in increasing agricultural productivity, their use has also raised concerns about environmental impact and health risks, leading to ongoing debates and regulatory measures.

The Green Revolution: Feeding the World

The Green Revolution, which began in the mid-20th century, represented a coordinated effort to improve crop yields through the development of high-yielding varieties of staple crops, improved irrigation techniques, and the increased use of fertilizers and pesticides. This agricultural revolution, led by scientists like Norman Borlaug, played a pivotal role in increasing food production worldwide, helping to avert widespread famine and addressing the food needs of a growing global population.

Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs): Customizing Crops

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) represent a more recent innovation in agriculture. GMOs are organisms whose genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally. In agriculture, this technology has been used to develop crops with traits such as resistance to pests, tolerance to herbicides, and improved nutritional content. GMOs have sparked considerable debate over their safety, environmental impact, and ethical considerations.

Precision Agriculture: The Digital Age of Farming

The digital revolution has brought agriculture into the realm of big data and advanced technology. Precision agriculture, also known as smart farming, leverages sensors, GPS technology, drones, and data analytics to optimize various aspects of farming, including planting, irrigation, and crop management. This data-driven approach allows farmers to make informed decisions, minimize resource wastage, and increase crop yields, ultimately contributing to sustainable and efficient agriculture.

Throughout history, agriculture has been a dynamic and ever-evolving field driven by innovation and necessity. The inventions discussed in this article represent a sampling of the many remarkable contributions that have shaped the way we grow and harvest food. As we confront contemporary challenges, such as climate change, food security, and sustainable agriculture, the spirit of innovation continues to drive the development of new technologies and approaches that will shape the future of agriculture. Whether through advancements in genetic engineering, digital agriculture, or sustainable practices, the journey of agricultural innovation is far from over. As we look ahead, we can expect agriculture to continue to adapt and transform, ensuring that the world’s growing population has access to safe, nutritious, and abundant food.

Farm & Ranch

The Working Dog

By Laci Jones

A dog is commonly referred to as “man’s best friend,” but is the saying still true for a working dog?

Randy Reed, an Oklahoma dog trainer for more than 10 years said having working dogs on the farm and ranch is helpful because of their ability to sort livestock. He said having a good working dog will make the trainer look good.

“These dogs will teach you just as much as you can teach them,” Reed said. “They are intelligent dogs, and all they want is to work and please you.”

Each dog has a different technique to herding livestock, Reed explained.

“Herding dogs were developed to do certain jobs for different types of livestock and for different types of farming,” said Susan Bennett, president of the Oklahoma Stock Dog Association.

Some dogs, known as headers, will herd livestock by putting pressure toward the stock’s head. Other dogs, known as heelers, will nip at the heels of stock to herd them. Bennett said some dogs can be headers and heelers. Each livestock species may require a different approach, Reed said.

“Working sheep is different than working cattle,” he said. “The dogs can work the sheep with their eyes. You don’t have to be on sheep so tight, but it’s a challenge with cattle.”

For an owner, it may be a challenge to decide which dog breed is appropriate to have. The best working dog breed depends on what livestock species is worked and the owner’s preferences.

Border Collie

Border collies are known for their herding ability, Bennett said. This breed of dog was bred for their intelligence and work ethic.

“The border collies that actually work livestock were never bred for how they looked,” she added.

Border collies typically use their eyes to herd livestock, but they can also be sent into a pasture and gather livestock.

“If you want to pull 300 yearlings off of a wheat pasture, you can pull up to the gate send the border collies out there,” Reed said. “They will bring the cattle right to you and through the gate.”

Bennett said people need to make sure they have jobs for working dogs.

“These dogs have been bred for hundreds of years, and they have to find an outlet for that instinct,” Bennett said.

When the border collies are not working, both Bennett and Reed keep their border collies in pens.

“I can run them loose, but they will overwork the stock,” Reed said. “They are like keeping an eye on kids.”

A downside to having a border collie is some may not have a tough enough bite, Reed said. They may not be as aggressive as other dog breeds.

Kelpie

Kelpies originated from Australia and are typically short, slick-haired dogs. This breed of dog is rangier than most other breeds, Reed said.

“Kelpies’ working style is similar to border collies,” he said.

Like border collies, kelpies are a “fetch” dog, meaning they will bring the livestock back to the owner, he said.

Bennett said the kelpies she has seen are typically more aggressive toward livestock. They have more stamina than most breeds, Reed added.

“When they go to work, they will be in a crouch position,” Reed said. “Their head is going to be down level with their shoulders. The tail is going to be dropped down behind them.”

Good border collies and kelpies have constant control, and they will have a lot of movement with their eyes, he said.

Reed said the American kelpie is close in proximity with the Australian kelpie. However, the American kelpie is weaker than the Australian kelpie.

Australian Cattle Dog

Developed from the native Australian dingo, the Australian cattle dogs was originally bred for driving livestock, Bennett said.

She said most working dogs within this breed are heelers, which is why they are commonly referred to as blue or red heelers, depending on their color.

Australian cattle dogs are typically used in pens and corrals to move livestock, Bennett said. They were not developed to go into open areas and gather livestock.

“We would haul cattle to the sale barn,” Reed said. “There was a blue heeler that would work on the chute and bite the cattle and get them through there.”

However, the Australian cattle dog is not as common in the competition trials as the border collie.

Reed said there is a market for the Australian cattle dog in the state. Australian cattle dogs are in high demand, but their herding ability is still to be determined.

Australian Shepherd

“Back when the United States was being settled, the Australian shepherd was the farm dog to have,” Bennett said.

Bennett said Australian shepherds were bred to be farm dogs, but they have changed in recent years to become show dogs and pets.

“There are very few Australian shepherds that can now go out and do a job,” Bennett said.

The Australian shepherd is not as popular for herding as other breeds today, Reed added.

“They are pretty dogs, but I haven’t seen any stock-oriented,” Reed said.

Reed said Australian shepherds can be trained, but he found them to be easily distracted.

Catahoula

Catahoulas are typically used for hunting. However, these bay-type dogs can be used to work livestock.

Reed said catahoulas and border collies have different styles of working. Unlike the border collie, this breed of dog uses their bark to move livestock, Reed said. Catahoulas will also work the outer perimeter of livestock, he said.

“Catahoulas will hunt livestock because they can use their nose, where the border collie will do everything by the power of their eyes,” Reed said.

Reed said catahoulas would be the better working dog in a situation where the owner needed help finding livestock.

However, working livestock with a catahoula is a team effort. A catahoula dog will not fetch livestock, but they will keep livestock in a “tight wad.” The owner will have to move the cattle themselves.

Cattlemaster

The cattlemaster is a newer breed of working dog. They are a cross between Border collie, pit bull, and kelpie, and they were bred for working cattle, according to Reed. They are more aggressive and have a stronger bite.

However, when cattlemaster was bred to get more bite, they lost their natural herding ability. Reed experienced this firsthand when he trained a cattlemaster.

“There wasn’t the natural ability,” Reed said. “She was just mechanical. I can move her, but she couldn’t read a cow.”

Reed said other breeds of dogs can potentially be used as working dogs including corgis, McNab shepherds and German shepherds. However, before purchasing a new dog, the buyer should research bloodlines and breeders.

“Buy a dog that can be bred to work cattle,” Reed advised. “Go watch the parents work and research who has trained the dogs.”

It is also important to purchase a dog that has been bred to work the specific species of livestock, Bennett added. No matter what dog breed an owner chooses, imported dogs may not always make the best working dogs.

“Just because a dog is imported doesn’t mean it will be better than a dog bred right here in the United States,” Bennett said.

She said there are many more great dogs and trainers in the United States than 20 years ago. It may be helpful to seek advice from a professional to help kick-start a new program, she added.

After purchasing a working dog, it is important to spend extra money to send the dog to a trainer for 30 to 60 days, Reed said. Then, the owner should spend quality time with the dog and the trainer to learn how to work together.

Bennett said each dog may require a different type of training, which may require adjusting. She said incorporating techniques from several different trainers can help the owner and their best friend.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 edition of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

-

Attractions8 years ago

Attractions8 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Country Lifestyle6 months ago

Country Lifestyle6 months agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Country Lifestyle9 years ago

Country Lifestyle9 years agoThe House a Treasure Built

-

Country Lifestyle3 years ago

Country Lifestyle3 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Outdoors7 years ago

Outdoors7 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Outdoors5 years ago

Outdoors5 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Farm & Ranch6 years ago

Farm & Ranch6 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)