Attractions

The Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society’s Oral History Collection

Listen not only to hear, but also to see and to act.

Listen to the words of the pioneers of Conservation and envision what they have seen and what they hoped for, and then practice it today and tomorrow on Oklahoma’s farms and ranches and within its growing urban areas.

That’s getting down to the subsoil or rather the essence of the Oklahoma Conservation Heritage Oral History Collection.

Just over two years ago the Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society announced the launch of this priceless conservation collection of passion, knowledge and effort.

The Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society partnered with the Oklahoma State University Library to record and archive interviews with individuals who have made contributions to conservation in Oklahoma. Audio, video, and transcripts of the interviews are posted digitally in the new Conservation Heritage Section of the OSU Library’s oral history collections. Interviews are available to researchers and the general public.

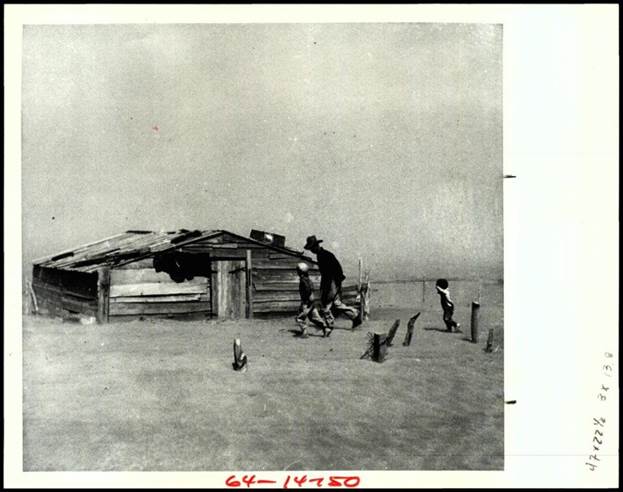

Oklahoma holds a unique place within the American conservation movement as the epicenter of the worst man-made ecological disaster in history, the Dustbowl. Out of the 1930s conservation districts were created by local farmers and ranchers who recognized the need to implement voluntary conservation practices on private working lands. Over the course of the last 80-plus years, Oklahoma has been a leader in the adoption of practices that benefit the health of our soils and water while building resiliency on our farms and ranches.

The Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society was formed in partnership with the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts, the Oklahoma Conservation Commission, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Oklahoma Chapter of the Soil and Waters Conservation Society and the RC&D Association. The Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society believes these interviews will preserve the storied and proud history of conservation in Oklahoma. This collection is a celebration of individuals and programs that have contributed to making Oklahoma known across the country as a leader in conservation.

Let us give you a couple of examples – Creede Speake, Jr., and Hal Clark – out of the many outstanding interviews you’ll hear in this collection.

Speake, born in Ardmore, Okla., in 1924 and a long-serving board member of the Caddo Watershed Association and of the Arbuckle Conservation District in Oklahoma, recalls his youth and his early interest in learning to be a pilot. He discusses some of his experiences serving during WWII and the Korean War and explains choices he made regarding his career as a rancher. Speake also talks about his involvement with conservation issues in his region and in the state and in particular his role in obtaining easements for upstream flood control structures.

A ways into the interview, Speake discusses managing grasslands. He said, “Native grass in this country is the most valuable thing you can have. You don’t have much at all, just management. Keep the weeds off of it, don’t have to fertilize it, but the four major native grasses we have here, they’re good. You get better gain and everything off of it. I wish everything I had was native grass. We’ve got a lot of Bermuda and other kinds of grass we have to fertilize.”

Clark, a graduate of Texas Tech University with a degree in Animal Science and Range Management, recalls his youth in the Panhandle of Oklahoma and Texas, relocating a couple times due to his father’s work, and his earliest memory of the impact of a flood. He discusses his early awareness of the issue of erosion and explains some conservation practices he has used to combat it. He also shares some of his experiences as a longtime member of the Cimarron County Conservation District (Oklahoma’s farthest western county) and his time as a member of the Oklahoma Conservation Commission.

Clark said, “We have a drier climate in Cimarron County, so it affects us in a lot of ways. The conservation challenges we have—Jimmy Emmons at (Dewey) County can grow a rotational crop that we can’t at Cimarron County because we don’t have the moisture. I wish we had rotation crops, something that could be plowed up (to improve the soil). I planted—on my farm, I planted Austrian winter peas a couple of times. Like that, it’s a legume. Cattle did pretty well on it, and I plowed it under to help the texture of the soil, because that’s the big issue now, people understanding what’s really underground—what’s in the soil that makes up what we’re trying to utilize to grow our crops or grass, so that’s a really important issue right now.”

Trey Lam has farmed on his family’s operation near Pauls Valley, Okla., for more than three decades and has served as the Executive Director of the Oklahoma Conservation Commission for more than five years. He has extensive knowledge of soil health, and he will quickly say that the bulk of it came from those two sources. He is quick to say that to lead in conservation you need to listen to soil health mentors and to the land itself.

“Please take the time to listen to these great Oklahomans tell their story of bringing our state back from an environmental disaster,” Lam said. “What a fantastic project teaching history in the first person. Conservationists want to leave the land better for the next generation. Now that generation can learn how these pioneers did it. We owe a huge thank you to the Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society.”

Sarah Blaney is Executive Director of the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts.

“Oklahoma’s conservation history is not just ours, but that of the entire nation,” Blaney said. “Many of the practices that have been adopted in soil and water conservation started right here in Oklahoma. It is wonderful that for generations to come, people will be able to learn from these conservationists. The Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society should be commended for doing an outstanding job preserving this important piece of rural, agriculture history.”

Ben Pollard is President of the Oklahoma Conservation Historical Society.

“We are most appreciative of the efforts of the Oral History Research Program at the OSU Library for working with us to create this collection,” Pollard said. “We have a proud conservation history in

To listen to the 23 completed oral histories, please visit: https://library.okstate.edu/oralhistory/digital/ or okconservation.org/history.

Read more in the July issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Attractions

What’s in a name?

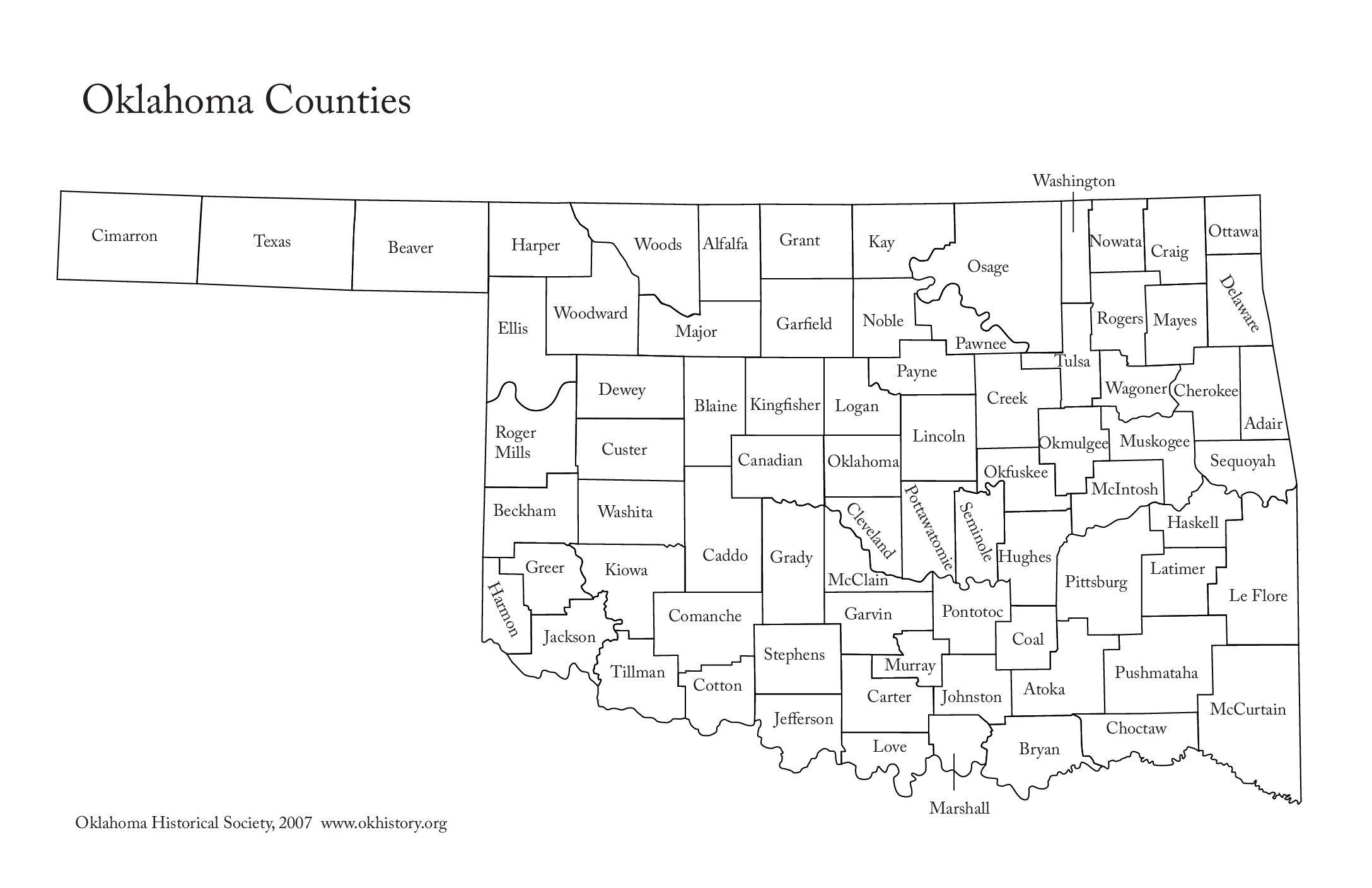

Each spring, Oklahomans can regularly be found listening to the radio or watching the television as weathermen and women report severe weather locations. Counties are typically used to identify storm locations, and while some names are easy to understand, others make us wonder.

While Oklahoma is ranked twentieth in size, it is seventeenth in the number of counties with 77. When it was first organized as the Oklahoma Territory, it had seven, which were designated numerically. When additional counties were added, they were given letters of the alphabet. When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, all the counties were renamed, with only two additional counties being added after statehood.

Oklahoma has 13 counties named for Indian tribes, and well-known Indian families have provided names for eight other counties. Six counties are named for U.S. Presidents, while rivers provided names for four counties. Military officers and Indian leaders are also honored.

Read on to learn what we found out about the etymology of our state’s counties.

Adair County was specifically named for Watt Adair, one of the first Cherokees to settle in the area.

Alfalfa County was formed at statehood as Woods County. The county is named after William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, the president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention and ninth governor of Oklahoma.

Atoka County honors a Choctaw Chief named Atoka.

Beaver County was given because of the presence of many beaver dams on the Beaver River, which runs through the area.

Beckham County was named for J. C. W. Beckham, who was Governor of Kentucky and the first elected member of the U.S. Senate.

Blaine County is the birthplace of voice actor Clarence Nash, the voice of Disney’s Donald Duck. It is named for James Blaine, the Secretary of State under President Harrison.

Bryan County was named for Democratic politician William Jennings Bryan.

Caddo County was named for the Caddo tribe who were settled here on a reservation in the 1870s.

Canadian County in the central part of the state is named for the Canadian River.

Carter County was named for Captain Ben W. Carter, a Cherokee who lived among the Chickasaw.

Cherokee County is named for the Cherokee Indian Nation.

Choctaw County’s name is derived from Chahta, the mythical founder of the Choctaw people.

The westernmost county in the state, Cimarron County contains the only community in the state that observes the Mountain Time Zone and is named for the Cimarron River.

Cleveland County was named after U.S. President Grover Cleveland.

Coal County was named for the mineral that was then the major product of the region.

Comanche County was named for the Comanche tribe.

At statehood, the area which is now Cotton County fell within the boundaries of Comanche County. It split off in 1912, becoming the last county created in the state; it was named for the county’s primary crop.

Craig County was named for Granville Craig, a prominent Cherokee farmer who lived in the Bluejacket area.

Creek County got its name from the Creek Nation, whose country following Indian removal included the county.

Custer County was named in honor of General George Armstrong Custer.

Delaware County was named for the Delaware Indians who had established a village in the area prior to the arrival of the Cherokees in Indian Territory in the 1830s.

Originally created in 1891 as “County D,” voters in an 1898 election chose the name Dewey County, honoring Admiral George Dewey.

Ellis County was named for Albert H. Ellis, vice president of the 1906 Constitutional Convention.

Garfield County was named after President James Garfield. Prior to the Land Run of 1893, Garfield County was named O County.

Garvin County was named for Samuel J. Garvin, a local Chickasaw rancher, merchant and banker.

Grady County was named for Henry W. Grady, an editor of the Atlanta Constitution and southern orator.

Grant County was named County L in Oklahoma Territory at the time of its opening to non-Indian settlement. A county election renamed it for U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant.

Greer County is named for Texas stateman and Lieutenant Governor of Texas John Greer.

Harmon County takes is name for Judson Harmon, governor of Ohio and U.S. Secretary of State.

Harper County was created from the northwestern part of Woodward County and named for Oscar Green Harper, who was clerk of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

Haskell County is named in honor of Charles N. Haskell, who was the first governor of Oklahoma.

Hughes County was named for W. C. Hughes, an Oklahoma City lawyer who was a member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

It’s unknown which Jackson Jackson County was named for: President Andrew Jackson or Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

Jefferson County was created at statehood and named in honor of President Thomas Jefferson.

Johnston County was named for Douglas H. Johnston, a governor of the Chickasaw Nation.

Kay County was originally designated as county “K.” Kay County is the only county to keep its same name as the Oklahoma area moved from a territory to a state.

Kingfisher County was formed in 1890 and named Kingfisher by a vote of residents.

Kiowa County was named for the Kiowa people.

Latimer County was created at statehood and named for James Latimer, a delegate to the state Constitutional Convention.

Le Flore County honors a Choctaw family of French descent named LeFlore.

Lincoln County was named for Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president of the United States.

Logan County was named for John Logan, Federal general in the War Between the States, and a U.S. Senator from Illinois.

Love County was named for Overton Love, a prominent Chickasaw farmer, entrepreneur and politician. His descendants built the nationwide Love’s Travel Stops.

Major County was named for John Major, a member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

Marshall County was named to honor the maiden name of the mother of George Henshaw, a member of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention.

Mayes County took its name for Samuel Houston Mayes, a teenage Confederate cavalryman, and mixed-blood Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

McClain County pays homage to Charles M. McClain, an Oklahoma constitutional convention attendee.

McCurtain County was named for an influential Choctaw family that lived in the area.

McIntosh County is named for an influential Muscogee Creek family whose members led the migration of the Lower Towns to Indian Territory and served as leaders for generations.

Murray County was named for William H. Murray, president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention and later a Governor of Oklahoma.

Muskogee County was named for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The official spelling of the name was later changed to Muskogee.

Originally designated as County P, Noble County was renamed for John Willock Noble, then the United States Secretary of the Interior.

Nowata County’s nameis derived from a Delaware word “no-we-ata,” meaning “come here” or “welcome.”

Okfuskee County is named for a former Muscogee town in Alabama, from which the Creek were removed to Indian Territory, that in turn was named for the Okfuskee, a Muscogee tribe.

Oklahoma County is one of seven counties in the United States to share the same name as the state it is located in (the other six counties are Arkansas County, Hawaii County, Idaho County, Iowa County, New York County, and Utah County), and the only one of the seven to contain the state capital.

Okmulgee County is named after a Creek town of the same name in Alabama, from which the Creek were removed to Indian Territory. The name Okmulgee is derived from the word okimulgi, meaning “boiling waters.

Osage County is the largest county by area in the state and is named for and is home to the federally recognized Osage Nation.

Ottawa County was named for the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma.

Pawnee County is named for the Pawnee tribe, which settled in the area following the War Between the States.

Payne County was named for Capt. David L. Payne, a leader of the “Boomers.”

Pittsburg County got its name because county leaders believed that its coal production compared favorably with Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at the time of statehood.

Pontotoc County was named for an historic Chickasaw tribal area in Mississippi.

Pottawatomie County got its name for the tribe that lived in the area. It’s name is a Chippewa term that means “people of the place of the fire.”

Pushmataha County was named for Pushmataha, an important Choctaw chief in the American Southeast.

Roger Mills County got its name for Confederate office and U.S. senator from Texas.

The area of Rogers County was named the Cooweescoowee District at the time of statehood, but the residents protested. It was renamed for Clem Vann Rogers, a prominent Cherokee rancher and father of Will Rogers.

Seminole County is named for the Seminole Nation, whose capital is also the county seat of Wewoka.

Sequoyah County was named to honor legendary statesman and creator of the Cherokee syllabary, which brought literacy to the Cherokee Nation.

Stephens County was named for Texas politician John Hall Stephens, who championed for Oklahoma statehood.

Texas County was named for its neighbor to the south.

Tillman County was named for U.S. Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina.

Tulsa County was named after the previously established city of Tulsa and the Creek village of Tulsey Town in Alabama.

Wagoner County is named for the county seat of the same name, which derived from Henry “Big Foot” Parsons.

Named for President George Washington, Washington County is the second smallest county in Oklahoma.

Washita County is named for the almost 300-mile long river that runs through it and empties into Lake Texoma and the Red River.

Woods County was named after Samuel Newitt Wood, a renowned Kansas activist, legislator, and newspaper publisher.

Woodward County was originally known as “N” County and was composed of present-day Woodward County and portions of Harper, Ellis, and Woods County. It is unknown exactly whom the county (and the town) is named after, but the two leading candidates are Brinton W. Woodward, a Santa Fe railway director, or Richard Woodward, a buffalo hunter.

Attractions

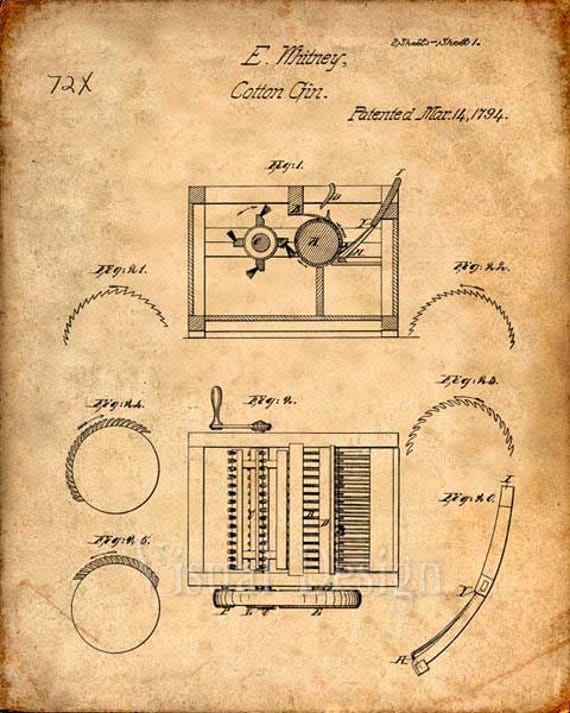

Inventions of Agriculture: The Cotton Gin

A few centuries ago, the landscape of farming and ranching looked quite different than it does today. There were no tractors for plowing, airplanes for spraying or even barbed wire for separating cattle.

There are inventions that have come along and changed the face of agriculture across the United States. One of those inventions was the cotton gin. It was invented during a time when the agricultural industry was struggling after its most significant crop, tobacco, saw revenues begin to plummet. But while it saved the profits and livelihood of many farmers and plantation owners, it also led to the increase in slave labor, making it an invention that significantly changed both our economic and social past.

The cotton gin was invented by Eli Whitney. Whitney was born in Westborough, Mass., on Dec. 8, 1765. His father was a farmer, and his son would prove his talents as both an inventor and a mechanic at a young age.

Whitney graduated Yale University and even considered becoming a lawyer, but life took him down a different path, one that would change the lives of farmers forever. He made his way to the south after graduation with plans to tutor, but upon arrival, he accepted a position with Catherine Green in Savannah, Ga. Greene was the widow of American Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene and owned the Mulberry Grove plantation.

At the time, tobacco was falling in value due to both soil exhaustion and abundance. Farmers began turning to other crop options, including cotton. Unfortunately, the only variety that could be grown inland contained seeds that were time-consuming to pick out.

During the colonial times, cloth derived from cotton was more expensive than wool or even linen due to the difficulty of removing these seeds from the fibers. It took an entire day just to detach seeds from one single pound of cotton. Whitney’s employer, Greene, urged the young Whitney to find a solution to this problem. Her support was crucial in Whitney’s success in inventing the cotton gin. Some even suggest that it was actually Greene who was the true inventor of the cotton gin, but at the time, women were not allowed to apply for patents in the United States.

On March 14, 1794, Whitney succeeded in obtaining a patent for the cotton gin. While similar devices had been around for many years, his was the first single device that could clean short-staple cotton. The introduction of the new technology made cotton a profitable crop in the United States for the very first time.

The device worked much like a strainer. The cotton was run through a drum, made of wood, which included hooks similar to teeth along the perimeter. Those hooks caught the cotton fiber and drug them through a mesh, which was too small to allow the seeds through. However, the hooks pulled the cotton through easily.

Small cotton gins could easily be worked by hand, while larger ones included the use of horses to power. Even the smaller gin could remove seeds from 50 pounds of cotton in one day, a much larger amount than the results of doing it by hand. In fact, the gin allowed 1,000 pounds of cotton to be cleaned in the same amount of time it took a worker to do five pounds by hand.

Due to Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin, along with other inventions of the Industrial Revolution such as machines to weave it, the price of cotton plunged and production of it doubled each decade after 1800. It even began being shipped overseas, and soon American farmers were growing 75 percent of the world’s supply of cotton.

However, Whitney’s invention was not all good news. While it did increase the production and profits of crops in America, it also established the cotton plantation culture of the south. The cotton crop became so lucrative for plantation owners, the demand to make more significantly increased. As it did, so did the use of slave labor for growing it.

As for Whitney, he struggled with patent-law issues that prevented him from significantly profiting from his invention. He managed to overcome that obstacle when he secured a contract with the United State government in 1798 to create 10,000 muskets.

While it would take him a decade to make those instead of the two years originally planned in the contract, he began endorsing interchangeable parts. In other words, identical parts could be quickly assembled while making for easier repairs on machines. Many objects, from machines to guns, were constructed by individuals. While Whitney is most known for his invention of the cotton gin, he also is credited for the development of mass production within America.

In his personal life, Whitney did not wed until his 50s, when he married Henrietta Edwards in 1817. The pair would go on to have four children before his death on Jan. 8, 1825, at the age of 59.

Resources

History. (2010, February 4). Cotton Gin and Eli Whitney. A&E Television Networks. https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/cotton-gin-and-eli-whitney

National Archives and Records Administration. (2021, December 16). Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton Gin. National Archives Educator Resources. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/cotton-gin-patent#background (Text adapted from an article written by Joan Brodsky Schur, a teacher at Village Community School in New York, N.Y.)

Attractions

Let’s Take A Trip – Part 1

After almost two years of Covid, testing, vaccinations, boosters, illness and death, wearing masks, staying indoors and away from others, severe thunderstorms, tornados, and now war in Europe, it’s time to get out and away from it all for at least a day.

Let’s get on I35 North of Ardmore and begin our trip in the Arbuckle Mountains. Stop at every scenic turnout to enjoy the awe-inspiring views of the trees, valleys, and rocks that according to archeologists formed during an earthquake eons ago.

Reached by a narrow twisty highway, a sight comparable to a miniature Niagara Falls is soon revealed. Cascading 77 feet, Turner Falls is majestic. Formed by Honey Creek, it empties into a beautiful blue lake.

Although it may be tempting, climbing to the area behind the falls and sliding down the falls is prohibited by law because more than one person has drowned attempting lt.

Be sure to visit Collins Castle, built in the early 30`s of native materials as a summer home for Dr. Elizabeth Collins, a professor at Oklahoma University. It was once headquarters for the Bar C Ranch.

The entire park covers 1,500 acres and includes swimming areas, camping areas, cabins, hiking trails, caves, a water slide, trout fishing, and Look Out Point, featuring telescopes allowing you to view the entire park.

A zip line, diving, scubas, and floating on inner tubes entertains many visitors.

Children play areas, a trading post and majestic scenery attract more than 250,000 visitors each year.

Come for a day or a week and enjoy all the park has to offer.

-

Country Lifestyle7 years ago

Country Lifestyle7 years agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Outdoors6 years ago

Outdoors6 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Country Lifestyle3 years ago

Country Lifestyle3 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Farm & Ranch6 years ago

Farm & Ranch6 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Outdoors3 years ago

Outdoors3 years agoSuzy Landess: Conservation carries history into the future