Farm & Ranch

From Plow to Plentiful: The Most Important Inventions in Agricultural History

Agriculture is the foundation of human civilization. Throughout history, the quest for more efficient and productive methods of farming has led to the invention of countless tools and technologies. These inventions have not only revolutionized agriculture but have also played a pivotal role in shaping societies and economies. In this comprehensive exploration, we will delve into some of the most important inventions related to agriculture that have had a profound and lasting impact on the way we grow and harvest food.

The Wheel and Axle: Unlocking Mobility and Productivity

The wheel and axle, one of the earliest inventions in human history, had a significant impact on agriculture. This invention, which dates back to around 3500 BC, revolutionized transportation, making it possible to move heavy loads and machinery more efficiently. In agriculture, the wheel and axle played a crucial role in the development of carts, wagons, and plows, enabling farmers to transport goods and cultivate larger areas of land.

The Plow: Cultivating the Earth’s Riches

The plow is arguably one of the most iconic agricultural inventions. Its origins trace back to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt around 3000 BC. The plow transformed agriculture by allowing farmers to dig deep furrows in the soil, turning it over and aerating it. This improved soil quality, making it more fertile and suitable for planting a wider variety of crops. The plow’s evolution from simple wooden implements to more sophisticated steel plows in the 19th century drastically increased the efficiency of farming.

Irrigation Systems: Mastering Water Management

Irrigation systems are a testament to human ingenuity in harnessing water for agriculture. The earliest known irrigation systems date back to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, around 6000 BC. These systems, which transported water from rivers to fields, allowed farmers to cultivate crops even in arid regions. Over time, irrigation methods have become increasingly sophisticated, incorporating canals, pumps, and drip irrigation systems, ensuring a consistent and controlled water supply for agriculture. Today, modern irrigation practices help feed billions of people around the world.

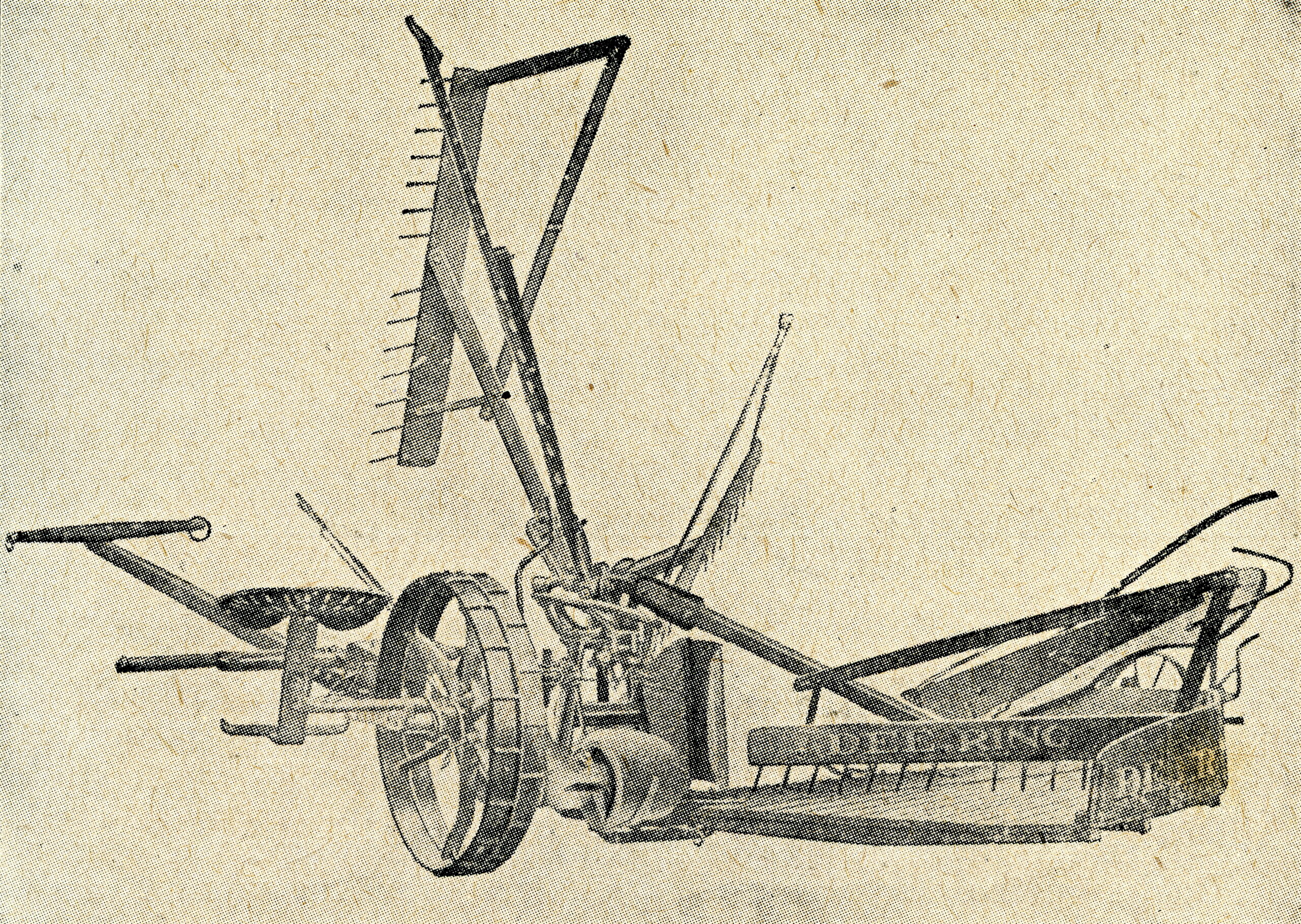

The Seed Drill: Sowing the Seeds of Precision

The seed drill, invented by Jethro Tull in the early 18th century, represented a leap forward in precision agriculture. Before its invention, seeds were sown by hand, resulting in uneven distribution and often wasteful planting practices. Tull’s seed drill, powered by horses, allowed farmers to sow seeds at a consistent depth and spacing, significantly increasing crop yields. This invention laid the groundwork for modern agricultural practices, emphasizing efficiency and precision in planting.

The Cotton Gin: Revolutionizing Textile Production

While not directly related to food production, the cotton gin, invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, had a profound impact on agriculture in the American South. This revolutionary machine automated the process of separating cotton fibers from their seeds, increasing the efficiency of cotton production by a factor of 50. The cotton gin’s success led to the widespread cultivation of cotton as a cash crop, shaping the economic landscape of the Southern United States.

The Mechanical Reaper: Harvesting the Bounty

The mechanical reaper, invented by Cyrus McCormick in the 1830s, mechanized the labor-intensive process of harvesting grain crops such as wheat. This invention featured a cutting mechanism that could efficiently harvest crops at a much faster rate than manual labor. The mechanical reaper played a pivotal role in increasing agricultural productivity during the 19th century and contributed to the expansion of agriculture in the United States.

The Steam Engine: Powering Progress

The steam engine, invented by James Watt in the late 18th century, revolutionized agriculture by providing a reliable source of power for various farming machinery. Steam engines were used to drive pumps for drainage, power threshing machines, and even locomotives for transporting agricultural goods to markets. The introduction of steam power marked a significant shift from human and animal labor to mechanical power, greatly increasing agricultural efficiency.

The Refrigerated Railcar: Expanding Food Distribution

In the late 19th century, the refrigerated railcar, often credited to Gustavus Swift, transformed the way food was transported and distributed. Before its invention, the transportation of perishable goods was a major logistical challenge. Refrigerated railcars allowed for the long-distance shipment of fresh produce, meat, and dairy products, opening up new markets and ensuring a more reliable food supply for urban populations.

Pesticides and Herbicides: Protecting Crops

The development of synthetic pesticides and herbicides in the 20th century marked a significant milestone in agriculture. These chemical compounds, such as DDT and glyphosate, helped farmers combat pests and weeds that threatened their crops. While these chemicals have played a vital role in increasing agricultural productivity, their use has also raised concerns about environmental impact and health risks, leading to ongoing debates and regulatory measures.

The Green Revolution: Feeding the World

The Green Revolution, which began in the mid-20th century, represented a coordinated effort to improve crop yields through the development of high-yielding varieties of staple crops, improved irrigation techniques, and the increased use of fertilizers and pesticides. This agricultural revolution, led by scientists like Norman Borlaug, played a pivotal role in increasing food production worldwide, helping to avert widespread famine and addressing the food needs of a growing global population.

Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs): Customizing Crops

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) represent a more recent innovation in agriculture. GMOs are organisms whose genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally. In agriculture, this technology has been used to develop crops with traits such as resistance to pests, tolerance to herbicides, and improved nutritional content. GMOs have sparked considerable debate over their safety, environmental impact, and ethical considerations.

Precision Agriculture: The Digital Age of Farming

The digital revolution has brought agriculture into the realm of big data and advanced technology. Precision agriculture, also known as smart farming, leverages sensors, GPS technology, drones, and data analytics to optimize various aspects of farming, including planting, irrigation, and crop management. This data-driven approach allows farmers to make informed decisions, minimize resource wastage, and increase crop yields, ultimately contributing to sustainable and efficient agriculture.

Throughout history, agriculture has been a dynamic and ever-evolving field driven by innovation and necessity. The inventions discussed in this article represent a sampling of the many remarkable contributions that have shaped the way we grow and harvest food. As we confront contemporary challenges, such as climate change, food security, and sustainable agriculture, the spirit of innovation continues to drive the development of new technologies and approaches that will shape the future of agriculture. Whether through advancements in genetic engineering, digital agriculture, or sustainable practices, the journey of agricultural innovation is far from over. As we look ahead, we can expect agriculture to continue to adapt and transform, ensuring that the world’s growing population has access to safe, nutritious, and abundant food.

Farm & Ranch

Fescue Foot

Barry Whitworth, DVM | Area Food/Animal Quality and Health Specialist for Eastern Oklahoma

*Article originally printed in the October 2022 issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Since most of Oklahoma experienced drought conditions and with fall fast approaching, producers with fescue pastures should closely observe their livestock for any signs of fescue toxicity. According to Mike Trammel, Pottawatomie County Ag Educator and Muti-County Agronomist, fescue toxins (ergot alkaloids) tend to increase in Kentucky-31 tall fescue pastures in the fall. Some reports indicate more problems with fescue toxins following a summer drought and limited fall rains. All of this may put Oklahoma cattle at a greater risk of fescue toxicity.

One issue that cattle experience with fescue toxins is fescue foot. Fescue foot is thought to be caused by ergot alkaloids such as ergovaline. These alkaloids are produced by endophyte fungus (Epichloë coenophiala) which is in tall fescue. Ergovaline has been proven to be a vasoconstrictor which might be responsible for fescue foot and heat intolerance also known as summer slump in cattle. Other issues that may be seen with the ergot fescue toxins are reduced milk production and reproductive issues.

Clinical signs of fescue foot appear within a few days of cattle being turned on to tall fescue pastures or it may take weeks if toxins in the pasture are low. Producers will initially observe cattle with arched back, rough hair coats, and sore feet. These symptoms are more noticeable early in the morning and with cold weather. This is followed by reddening and swelling in the area between the dewclaws and hooves. The lameness usually becomes more severe with time. If no action is taken, gangrene will result in loss of tissues distal to the coronary band and declaws. If the weather remains mild, other signs such as increase respiration rate, increase heart rate, and higher body temperature are more common.

Other causes of lameness in cattle must be differentiated from fescue foot. One simple method that will help differentiate fescue foot from footrot is to check the temperature of the foot. If the foot is cold, this is an indication that the problem is more likely fescue foot.

Since there is not a specific treatment for fescue foot, the condition must be managed. Cattle need to be observed daily for any signs of lameness or stiffness during the first few weeks on fescue pastures. This should be done early in the morning before cattle walk off the stiffness. Producers should pay close attention during cold weather, especially when rain, snow, or ice are present. Any animal showing clinical signs of fescue foot should be removed from the pasture and placed in a clean environment. The animal should be fed a ration with no fescue toxins.

The best but most costly solution to reduce fescue toxicity is to renovate old pastures with new endophyte friendly varieties. If this option is not possible, producers might try interseeding fescue pastures with clovers or other grasses. This should dilute fescue toxins. Nitrogen fertilization may increase ergot alkaloids, so producers should avoid fertilizing fescue pastures with high amounts of nitrogen. Researchers have demonstrated that feeding a supplement while grazing fescue pastures reduces clinical symptoms. Some studies indicate a difference in susceptibility to fescue toxicity in some cattle. Selecting cattle based on genetic tolerance of fescue toxins is an option. (For more information go to www.agbotanica.com/t-snip.aspx)

With large areas in Oklahoma covered with Kentucky-31 fescue pastures, fescue foot as well as other fescue toxicities are not going away any time soon. Livestock producers will need to watch their livestock closely for any signs of fescue toxicity and manage their pastures to keep toxins as low as possible. If producers would like more information on fescue foot, they should consult their veterinarian and/or visit their local Oklahoma State University Cooperative County Extension Agriculture Educator.

Farm & Ranch

Animal Disease Traceability

Barry Whitworth, DVM, MPH | Senior Extension Specialist | Department of Animal & Food Sciences | Freguson College of Agriculture

On July 6, 2020, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) posted in the Federal Register a proposal that radio frequency identification tags be used as official identification for cattle and bison. Following a period for public comment, the USDA APHIS released a statement on April 24, 2024, with the amended animal disease traceability (ADT) regulation for cattle and bison. The full press release may be found at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/agency-announcements/aphis-bolsters-animal-disease-traceability-united-states. Under the new rule, cattle and bison will need to be identified with tags that are both visual and electronic.

The USDA defines ADT as knowing where diseased and at-risk animals are, where they have been, and when the animal disease event took place. A system that allows for efficient traceability of livestock in the United States (US) is essential for animal health and reducing the economic effect of a foreign animal disease outbreak and other diseases on livestock producers as well as others whose well-being depends on livestock production.

In the past, the USDA used metal tags commonly referred to as “Brite” or “Silver” tags to officially identify cattle and bison. Also, cattle and bison vaccinated for brucellosis were tagged with an orange USDA metal tag. Recently, the USDA recognized electronic identification (EID) as an official ID. Under the new rule, cattle and bison needing an USDA official ID will be tagged will an EID.

According to Dr. Rod Hall, State Veterinarian of Oklahoma, the average cattle producer will not notice any change under the new rule and will not have to do anything differently than they are currently doing. The rule does not require mandatory tagging of cattle on a farm or ranch. Livestock auctions will continue to tag cattle that require an official USDA ID. The only change is that an EID will be used instead of a metal tag. The classes of cattle and bison requiring USDA official ID have not changed. The classes are:

Beef Cattle & Bison

- Sexually intact 18 months and older

- Used for rodeo or recreational events (regardless of age)

- Used for shows or exhibitions

Dairy Cattle

- All female dairy cattle

- All male dairy cattle born after March 11, 2013

Other common reasons that cattle and bison require USDA official ID include disease testing for brucellosis or tuberculosis and movement from one state to another state. Also, brucellosis or calfhood vaccination of heifers require official ID. The official USDA ID will be an EID starting November 2024.

If a cattle producer would like to tag their breeding cattle, electronic ID tags are available from Dr. Rod Hall. Producers will have to pay the shipping cost but the tags are free. The order form is available at: https://ag.ok.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/MULTI-TAG-ORDER-FORM-v8.23.pdf. Producers with questions should call Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry at 405-522-6141.

Change is usually hard. Changing how cattle and bison are officially identified will be difficult for some cattle producers. However, in the event of a disease outbreak, the use of EID should make the traceability process more efficient which is a good thing.

Producer wanting more information on the USDA amended rule on animal disease traceability should go to: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/traceability#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20animal%20disease%20traceability%20system%20is%20our,sick%20and%20exposed%20animals%20to%20stop%20disease%20spread.

Farm & Ranch

Cattle Nematodes (Worms)

Barry Whitworth, DVM | Senior Extension Specialist | Department of Animal & Food Sciences

According to the Mesonet, Oklahoma received some much-needed rain in late April (2023). With the moderate temperatures and high humidity, the environment is perfect for the proliferation of gastrointestinal nematodes (GIN) which are commonly called “worms.” Cattle can be infected with a variety of GIN. Most do not cause issues unless husbandry practices are poor. However certain GIN have been associated with disease. The most pathological GIN in cattle is Ostertagia ostertagi. Cooperia species and Haemonchus species are two that have been implicated with production issues. Control of these parasites is constantly changing due to environment, anthelmintic (dewormer) resistance, and consumer preference. Cattle producers should develop a plan to manage these parasites.

In order for GIN to complete their life cycle, certain environmental conditions must exist. The development stage begins with passing of the egg in the feces of the animal. If the egg is to hatch, the temperature must be warm and the humidity needs to be close to 100%. Ideal temperature ranges from 70⁰ to 80⁰ Fahrenheit (F), but any temperature above 45⁰ F will allow for development. Temperatures above 85⁰ F or below 45⁰ F will begin to hamper development. Humidity needs to be 80% or higher.

Once the egg hatches, the larva goes through a couple of molts to reach the infective stage which is the third stage larva (L3). L3 must have moisture to free itself from the fecal pat. Once free, it rides a wave of water on to a blade of forage. Once ingested, this begins the prepatent or pre-adult stage. Two molts take place during this stage (L3 to L4 and L4 to L5). If conditions are not favorable for survivability of offspring, L4 will go into an arrested development stage (hypobiosis) for a period of time. The patent or adult stage is the mature breeding adult.

Once inside the body, the parasite will migrate to certain locations in the digestive tract. For example, O. ostertagi develop in the gastric gland in the abomasum. H. placei and H. contortus will migrate to the abomasum. Cooperia species will live in the small intestine. A few like Trichuris (whipworms) are found in the large intestine.

Clinical signs of parasitism vary according to the species of parasite, burden, and site of attachment. Severe disease, which is referred to as parasitic gastroenteritis (PGE), with internal parasites is unusual with today’s control methods. Clinical signs of PGE are lack of appetite, weight loss, weakness, diarrhea, submandibular edema (bottle jaw), and death. However, most parasite infection are subclinical which means producers do not see clinical signs of disease. In subclinical infections, the parasite causes production issues such as poor weight gain in young cattle, reduced milk production, and lower pregnancy rates.

Producers should be monitoring their herds for parasites throughout the year but especially in the spring when conditions are ideal for infection. A fecal egg count (FEC) is a good way of accessing parasite burdens. Livestock producers need to gather fecal samples from their herd periodically. The samples should be sent to their veterinarian or a veterinary diagnostic lab. Different techniques are used to access the number of eggs per gram of feces. Based on the counts, the producer will learn the parasite burden of the herd. Producers can use this information to develop a treatment plan.

In the past, GIN control was simple. Cattle were routinely dewormed. Unfortunately, anthelmintic resistance has complicated parasite control. Now proper nutrition, grazing management, a general understanding of how weather influences parasites, biosecurity, refugia, anthelmintic efficiency, and the judicious use of anthelmintics are important in designing an effective parasite management program. All of these considerations need to be discussed in detail with a producer’s veterinarian when developing a plan for their operation.

Cattle producers need to understand that parasites cannot be eliminated. They must be managed with a variety of control methods. Designing a parasite management plan requires producers to gain a general understanding of life cycle of the parasite as well as the environmental needs of the parasite. Producers should use this information as well as consult with their veterinarian for a plan to manage GIN. For more information about GIN, producers should talk with their veterinarian and/or with their local Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Agriculture Educator.

References

Charlier, J., Höglund, J., Morgan, E. R., Geldhof, P., Vercruysse, J., & Claerebout, E. (2020). Biology and Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Nematodes in Cattle. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Food animal practice, 36(1), 1–15.

Navarre C. B. (2020). Epidemiology and Control of Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Cattle in Southern Climates. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Food animal practice, 36(1), 45–57.

Urquhart, G. M., Armour, J., Duncan, J. L., Dunn, A. M., & Jennings, F. W. (1987). In G. M. Urquhart (Ed). Veterinary Helminthology. Veterinary Parasitology (1st ed., pp 3-33). Longman Scientific & Technical.

-

Country Lifestyle7 years ago

Country Lifestyle7 years agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Outdoors6 years ago

Outdoors6 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Country Lifestyle3 years ago

Country Lifestyle3 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Farm & Ranch6 years ago

Farm & Ranch6 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Outdoors3 years ago

Outdoors3 years agoSuzy Landess: Conservation carries history into the future