Attractions

Express Clydesdales

By Amanda Martin

Winston Churchill once said, “There is something about the outside of a horse that is good for the inside of a man.”

That describes the feeling visitors get when entering the Express Clydesdale Barn in Yukon, Okla.

The barn, originally built in 1936, was restored by Amish carpenters especially for the Express Clydesdales in the late ‘90s. It features gorgeous pine wood walls, walnut trim and brass fixtures. Though beautiful inside and out, the horses inside are what make it worth a visit.

The Express Clydesdales have been a working team since 1998.

“It all began when Bob Funk, founder of Express Employment, was attending a horse show in Canada called Agribition,” said Benjamin Minshull, the Express Clydesdales trainer. “[When he was] introduced to the Clydesdale breed, he immediately fell in love with them and decided he’d like a hitch of his own to represent the company.”

To learn more about the Express Clydesdales, read the OKFR March issue.

Attractions

Inventions of Agriculture: The Cotton Gin

A few centuries ago, the landscape of farming and ranching looked quite different than it does today. There were no tractors for plowing, airplanes for spraying or even barbed wire for separating cattle.

There are inventions that have come along and changed the face of agriculture across the United States. One of those inventions was the cotton gin. It was invented during a time when the agricultural industry was struggling after its most significant crop, tobacco, saw revenues begin to plummet. But while it saved the profits and livelihood of many farmers and plantation owners, it also led to the increase in slave labor, making it an invention that significantly changed both our economic and social past.

The cotton gin was invented by Eli Whitney. Whitney was born in Westborough, Mass., on Dec. 8, 1765. His father was a farmer, and his son would prove his talents as both an inventor and a mechanic at a young age.

Whitney graduated Yale University and even considered becoming a lawyer, but life took him down a different path, one that would change the lives of farmers forever. He made his way to the south after graduation with plans to tutor, but upon arrival, he accepted a position with Catherine Green in Savannah, Ga. Greene was the widow of American Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene and owned the Mulberry Grove plantation.

At the time, tobacco was falling in value due to both soil exhaustion and abundance. Farmers began turning to other crop options, including cotton. Unfortunately, the only variety that could be grown inland contained seeds that were time-consuming to pick out.

During the colonial times, cloth derived from cotton was more expensive than wool or even linen due to the difficulty of removing these seeds from the fibers. It took an entire day just to detach seeds from one single pound of cotton. Whitney’s employer, Greene, urged the young Whitney to find a solution to this problem. Her support was crucial in Whitney’s success in inventing the cotton gin. Some even suggest that it was actually Greene who was the true inventor of the cotton gin, but at the time, women were not allowed to apply for patents in the United States.

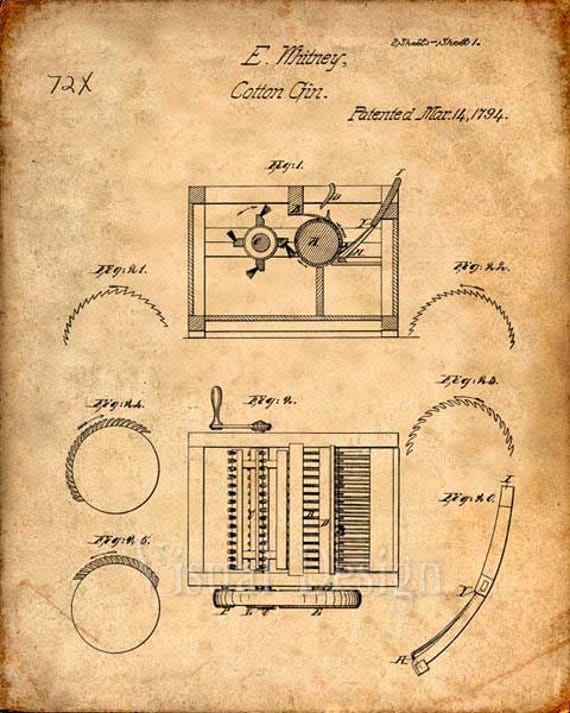

On March 14, 1794, Whitney succeeded in obtaining a patent for the cotton gin. While similar devices had been around for many years, his was the first single device that could clean short-staple cotton. The introduction of the new technology made cotton a profitable crop in the United States for the very first time.

The device worked much like a strainer. The cotton was run through a drum, made of wood, which included hooks similar to teeth along the perimeter. Those hooks caught the cotton fiber and drug them through a mesh, which was too small to allow the seeds through. However, the hooks pulled the cotton through easily.

Small cotton gins could easily be worked by hand, while larger ones included the use of horses to power. Even the smaller gin could remove seeds from 50 pounds of cotton in one day, a much larger amount than the results of doing it by hand. In fact, the gin allowed 1,000 pounds of cotton to be cleaned in the same amount of time it took a worker to do five pounds by hand.

Due to Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin, along with other inventions of the Industrial Revolution such as machines to weave it, the price of cotton plunged and production of it doubled each decade after 1800. It even began being shipped overseas, and soon American farmers were growing 75 percent of the world’s supply of cotton.

However, Whitney’s invention was not all good news. While it did increase the production and profits of crops in America, it also established the cotton plantation culture of the south. The cotton crop became so lucrative for plantation owners, the demand to make more significantly increased. As it did, so did the use of slave labor for growing it.

As for Whitney, he struggled with patent-law issues that prevented him from significantly profiting from his invention. He managed to overcome that obstacle when he secured a contract with the United State government in 1798 to create 10,000 muskets.

While it would take him a decade to make those instead of the two years originally planned in the contract, he began endorsing interchangeable parts. In other words, identical parts could be quickly assembled while making for easier repairs on machines. Many objects, from machines to guns, were constructed by individuals. While Whitney is most known for his invention of the cotton gin, he also is credited for the development of mass production within America.

In his personal life, Whitney did not wed until his 50s, when he married Henrietta Edwards in 1817. The pair would go on to have four children before his death on Jan. 8, 1825, at the age of 59.

Resources

History. (2010, February 4). Cotton Gin and Eli Whitney. A&E Television Networks. https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/cotton-gin-and-eli-whitney

National Archives and Records Administration. (2021, December 16). Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton Gin. National Archives Educator Resources. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/cotton-gin-patent#background (Text adapted from an article written by Joan Brodsky Schur, a teacher at Village Community School in New York, N.Y.)

Attractions

Let’s Take A Trip – Part 1

After almost two years of Covid, testing, vaccinations, boosters, illness and death, wearing masks, staying indoors and away from others, severe thunderstorms, tornados, and now war in Europe, it’s time to get out and away from it all for at least a day.

Let’s get on I35 North of Ardmore and begin our trip in the Arbuckle Mountains. Stop at every scenic turnout to enjoy the awe-inspiring views of the trees, valleys, and rocks that according to archeologists formed during an earthquake eons ago.

Reached by a narrow twisty highway, a sight comparable to a miniature Niagara Falls is soon revealed. Cascading 77 feet, Turner Falls is majestic. Formed by Honey Creek, it empties into a beautiful blue lake.

Although it may be tempting, climbing to the area behind the falls and sliding down the falls is prohibited by law because more than one person has drowned attempting lt.

Be sure to visit Collins Castle, built in the early 30`s of native materials as a summer home for Dr. Elizabeth Collins, a professor at Oklahoma University. It was once headquarters for the Bar C Ranch.

The entire park covers 1,500 acres and includes swimming areas, camping areas, cabins, hiking trails, caves, a water slide, trout fishing, and Look Out Point, featuring telescopes allowing you to view the entire park.

A zip line, diving, scubas, and floating on inner tubes entertains many visitors.

Children play areas, a trading post and majestic scenery attract more than 250,000 visitors each year.

Come for a day or a week and enjoy all the park has to offer.

Attractions

A Versatile Venue

Fields that once were prolific with wheat have now found a new purpose at P Bar Farms in Hydro, Okla. Now, colorful sunflowers abound, attracting visitors from all across the state who come for photo opportunities. In another 10-acre section, specialty corn is grown specifically to be mowed to a specific pattern, transforming into a maze that sees upwards of 15,000[LM1] visitors annually.

It’s not that Loren and Kim Liebscher couldn’t make a traditional farm work; it’s more that they were looking for something fun to do for a few years.

P Bar Farms is named for Travis Payne, Kim’s father. “We used to farm traditionally here. We were farming and her dad got sick. I kind of lost my love to farm, so I began praying that God would give me something to put the fun back into farming,” Loren shared.

It was just two weeks later that God delivered a sign that would change the course for P Bar Farm. “I read in a Progressive Farmer magazine about a guy doing a corn maze in Nashville, Tenn. We found out that the first Annual Corn Maze Convention was only two or three weeks after that,” he said. “So, we drove to Salt Lake City for the first convention, and that’s how we got started.”

Loren and Kim admit they knew nothing about corn mazes, but they learned plenty during the convention. “The Convention was actually part of a franchise company that was looking to add farms. We joined, and for the fee they gave us all the secrets and designs for the maze and everything,” Loren explained.

After a few years, the Liebschers opted out of the franchise. “We felt like we knew what we were doing by then,” Kim said.

The first P Bar Farms corn maze was grown and cut in 2001, but then 9/11 happened. The uncertainty that plagued the country made its way to Hydro, and it wasn’t a given that the corn maze adventure would even get out of the gate. “We thought that was going to be the end. We had hoped that if we got 1,000 people to come during that first season, at $5 a person, we’d be doing well. A $5,000 addition to your income is pretty good for a farmer,” Loren said. “That first year we wound up having close to 5,000, even with 9/11. We had one customer explain it to us. She said, ‘I’ve never felt so safe having my kids so lost, but it’s a family farming operation, and nothing’s going to happen here on the farm. It has that good feeling where people feel safe and comfortable.”

Kim added, “We just wanted to have something fun that was light-hearted. We didn’t anticipate being busy – we were just having fun. We thought we could do it, but if not, we don’t have anything to lose.”

With the success of the first year, the Liebschers knew they would do the corn maze again. They built a barn and added a new concession stand. They also interviewed some tough critics; teachers that came out to the farm. “We had a retired schoolteacher that worked for us, and she said if you want to get the truth to interview teachers. So, we created a survey that all the teachers filled out, and everything that came back said it was wonderful, a great concept, and a great idea,” Loren said. “But, they added they weren’t coming back until we got indoor bathrooms. That was the number one request from the teachers, so we definitely made that change.”

As the interest in the corn maze grew, P Bar Farms continued to expand. First a petting zoo was added, and then a new barn. With more requests for parties, more buildings went up. The Liebschers wanted the property to resemble an old family farm, so they purchased an old home in Hinton, Okla., and moved it in. “We wanted to use it as a bed and breakfast. That never really worked out, but we rented it for a while. Now it’s regularly booked as an Airbnb. People like to get away and get out in the country,” Kim shared.

There have been very few noticeable failures in the past two decades. The only other memorable one was a venture with a greenhouse. “With the wind in Oklahoma, that didn’t work for us. We had put asphalt in the bottom of our greenhouse, so we used that and put in a new party barn,” Loren said.

Soon a pumpkin patch was added to compliment the maze and the rest of the farm. “We’ve always had a pumpkin patch. The problem is pumpkins can be really hard to grow if you don’t rotate them, so we don’t do that real well. Our first year we had more than we could sell, but after that we really were going through them. Now we’re going through 15-20,000 pumpkins a year, and we can’t grow that many, so we just buy them,” Loren added.

It was only a few years ago that the Liebschers added a sunflower patch to the mix, taking up a few more acres covered by the pivot. “The first year they were fun and pretty, but we didn’t have a lot of visitors. This year has been different, and I think our daughter is probably the reason for that success. She has a marketing degree and it’s been unbelievable,” Kim said. “Oklahoma Tourism did a post about a ‘mystical sunflower patch.’ Now people are here all the time while they’re blooming to take photos.”

The sunflower patch is just a few acres, but the Liebschers feel it’s the perfect size. “We have found that the smaller the patch, the better people take care of it,” he said. “Plus, sunflowers are tricky. They either make it or they don’t, but this has been a very good year for them.

Read more in the October issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

-

Country Lifestyle7 years ago

Country Lifestyle7 years agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Outdoors6 years ago

Outdoors6 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Country Lifestyle2 years ago

Country Lifestyle2 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Farm & Ranch5 years ago

Farm & Ranch5 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Country Lifestyle1 year ago

Country Lifestyle1 year agoSay Yes!