Farm & Ranch

Efficiency at its Finest

Bert Hutson has always had an affinity for livestock nutrition, a passion that can be traced back to his days as an FFA member and working on his father’s dairy farm. That interest has helped Huston create and grow a large herd of Angus cattle that regularly bring premium prices not only at his annual sale but also in private treaty transactions.

At 80 years old, the Elk City rancher has no plans to slow down. His seventh annual bull sale, held in January, averaged nearly $1,000 more per bull than the previous year, and he and his team are constantly working to improve their product.

While Bert himself is progressive, he also believes in doing what works for his program – not following in the path of others.

The Beginning of the Cattle Business

Bert was born in 1939 and grew up working on his father, Martin Hutson’s, dairy farm in the early 1940s. “It was hard work. Whether you liked them or not, you milked cows every morning before you went to school. I fed sileage with a pitchfork and a little trailer and dipped it out. I would feed and milk in the morning and smell like sileage all day at school,” he recalled.

That first dairy farm was near Canute, Okla. “We milked cows so we could have a little money to buy groceries with. We didn’t have electricity then and milked cows with a gasoline motor running a vacuum pump. We got electricity in the latter part of 1948, and we felt like there’d never be another poor day,” Bert shared.

Soon after, around 1950, the elder Hutson built a dairy barn with a concrete floor. A health inspector named Troy Hicks came out to inspect the operation. “There was a lot of milk being sold in Elk City at the time, but it was Grade C, which is what they make cheese with. My dad got to sell the first Grade A milk in Elk City to Braden Dairy,” he said.

The dairy business rocked along steadily for several years, but when Martin received a terrifying diagnosis, it seemed that life was going to change.

Bert himself had just graduated high school and was only four days into a job of unloading lumber for a lumberyard in Clinton. “In 1959 dad was having some trouble seeing, and it wound up that he had pituitary gland cancer. He got a message that he had to go to the doctor in the city then or it would be too late,” Bert said.

Back then, a daily trek to and from Oklahoma City would have been too much, and Martin was advised to sell his dairy. “I told him ‘No, you’re not going to do that.’ I knew my job at the time wasn’t important, so he went to the doctor and I went to the dairy and milked his cows and fed them,” he said.

A couple months went by before Martin was able to travel home to check on his dairy, including a small herd of heifers Bert had been caring for. “You know, back then you just raised everything as poor as you could. He didn’t have much money, but I went and bought some cottonseed meal and mixed it with his sileage and fed those heifers.” He added, “What was real funny was when he came down to the lots and looked around. He saw those heifers and asked where I got them. He didn’t believe they were the same ones that were there when he’d left.”

Bert knew the cottonseed meal would add some much-needed protein to the heifers’ diet. “We just fed them silage, which wasn’t high protein, so I just added some stuff to it. I was always interested in that stuff in FFA. We’d figure out rations and things. He (Martin) always said, ‘I can’t believe those heifers look like that,’” Bert said.

Luckily, the Hutsons managed to save the dairy. Martin finally sold it in 1964 and moved north to Kansas. “He always liked to farm the black land and he took all his dairy equipment. He tried to get me to come up there and help him with a dairy, but I never did go,” he said.

Bert stayed in Oklahoma working as a truck driver for his uncle and dipped his toes into several other ventures. “I was into one thing and then the other. I did a little custom hay baling. I had a little trouble where they couldn’t keep my heart slowed down, and they told me I had to get out of the trucks and exercise, so I bought a 24 hour truck stop, and I got a lot of exercise doing that,” Bert said.

While the truck stop business was doing well, tragedy struck when one of the workers was shot and killed during an armed robbery. After that, Bert had trouble finding anyone to work overnight. Luckily, he had many friends who wanted him to get back into the hay business, so he and a friend started custom cutting and baling.

“Then in April of 1971, I had a neighbor move here from Texas who was an oilfield guy who was a mud engineer. He called me up and said, ‘You kick that hay off that truck and come haul mud for us.’ I said, ‘Well, golly, it’s nine o’clock at night,’ and he just told me that’s the mud business,’” Bert laughed.

After agreeing, Bert took off to Canadian, Texas, but it was raining and misting, and his truck didn’t have a heater or a defroster. “So, I just turned around and came back. I said, ‘Hey, you want your mud hauled? Call during the day,’” he laughed. “They told me to fix the heater and that was in the fall of 1971, and I haven’t been caught up since. I started out with an old $400 GMC hay truck.”

Bert was custom baling and hauling mud, which meant that his wife, Sue, and his son, Johnny, also had to pitch in. “The oilfield guys would call me at three or four in the afternoon, and I’d have to get on the truck. If I was baling or cutting, I’d tell my wife and she would come finish running the baler or the swather. When our son got a little older, around nine, he and a neighbor boy would come with my wife and she would let one of them run the tractor one round, and then the other would run it one round. The last guy that I can remember that was always telling people about Sue baling passed away about six months ago at 91 years old,” Bert said.

Read more in the March issue of Oklahoma Farm & Ranch.

Farm & Ranch

Hazards of Backyard Poultry

Barry Whitworth, DVM, MPH

Senior Extension Specialist, Department of Animal & Food Sciences, Ferguson College of Agriculture

Having backyard poultry is a popular agriculture enterprise. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, 0.8 percent of all households in the United States have chickens. People keep chickens for a variety of reasons with table eggs being one of the more common reasons. Unfortunately, some of these poultry producers are not aware of the hazards that come with keeping poultry because many times they carry pathogens but appear healthy.

Chickens are carriers of several zoonotic diseases. These are diseases that can be passed from animals to humans. According to a recent survey in Pennsylvania, a majority of backyard poultry producers were aware of the dangers of avian influenza. However, this study also revealed that far fewer producers were aware of the risk of possible exposure to Salmonella and Campylobacter. The lack of knowledge about the hazards of raising poultry likely contributes to the continued issues of Salmonella outbreaks associated with backyard poultry. In 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 1,072 illnesses of Salmonella linked to backyard poultry, and 272 of those patients required hospitalization. Oklahoma reported 43 individuals with the disease.

Direct contact with chickens is not the only way to be exposed to the pathogens they carry. The environment in which they live can be a danger due to air quality and waste in the soil. The air in a poultry coop is composed of dust particles, ammonia, pathogens, poultry droppings, and other materials. Breathing the dust while cleaning a poultry coop has been associated with respiratory issues in poultry workers. One study found that human infections are associated with contact with poultry waste and soil. Backyard poultry producers may be exposed to poultry droppings when cleaning equipment or pens.

Most zoonotic diseases can be prevented. Proper hand hygiene is one of the best disease prevention tools available. According to the Pennsylvania study, most poultry producers wash their hands after having contact with their birds. However, that same study found most poultry producers do not wear gloves or cover their mouths when handling animals or animal manure. Backyard poultry producers should wear proper protective equipment when cleaning equipment and pens.

Poultry producers can protect themselves by following some simple rules.

- Wash hands with soap and water before and after having any contact with poultry or any area where poultry are located. If soap is not available, use hand sanitizer.

- Do not kiss or snuggle birds.

- Do not allow poultry to enter areas where food and drinks are prepared, served and stored.

- Do not eat or drink where poultry are located.

- Cook eggs thoroughly.

- Clean equipment associated with poultry outdoors.

- Older adults, pregnant women, children under five, and immunocompromised individuals should be extra careful around poultry.

- Wear protective clothing, shoes, gloves, and a face mask when cleaning poultry houses.

Having chickens in the backyard can be very rewarding experiences. However, poultry owners should be aware of the potential hazards associated with backyard poultry production and protect themselves. If poultry producers would like more information about hazards associated with backyard poultry, contact your local veterinarian and/or Oklahoma State University County Extension Agriculture Educator. Also, the CDC has a website dedicated to backyard poultry producers’ health. The website can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/farm-animals/backyard-poultry.html.

Farm & Ranch

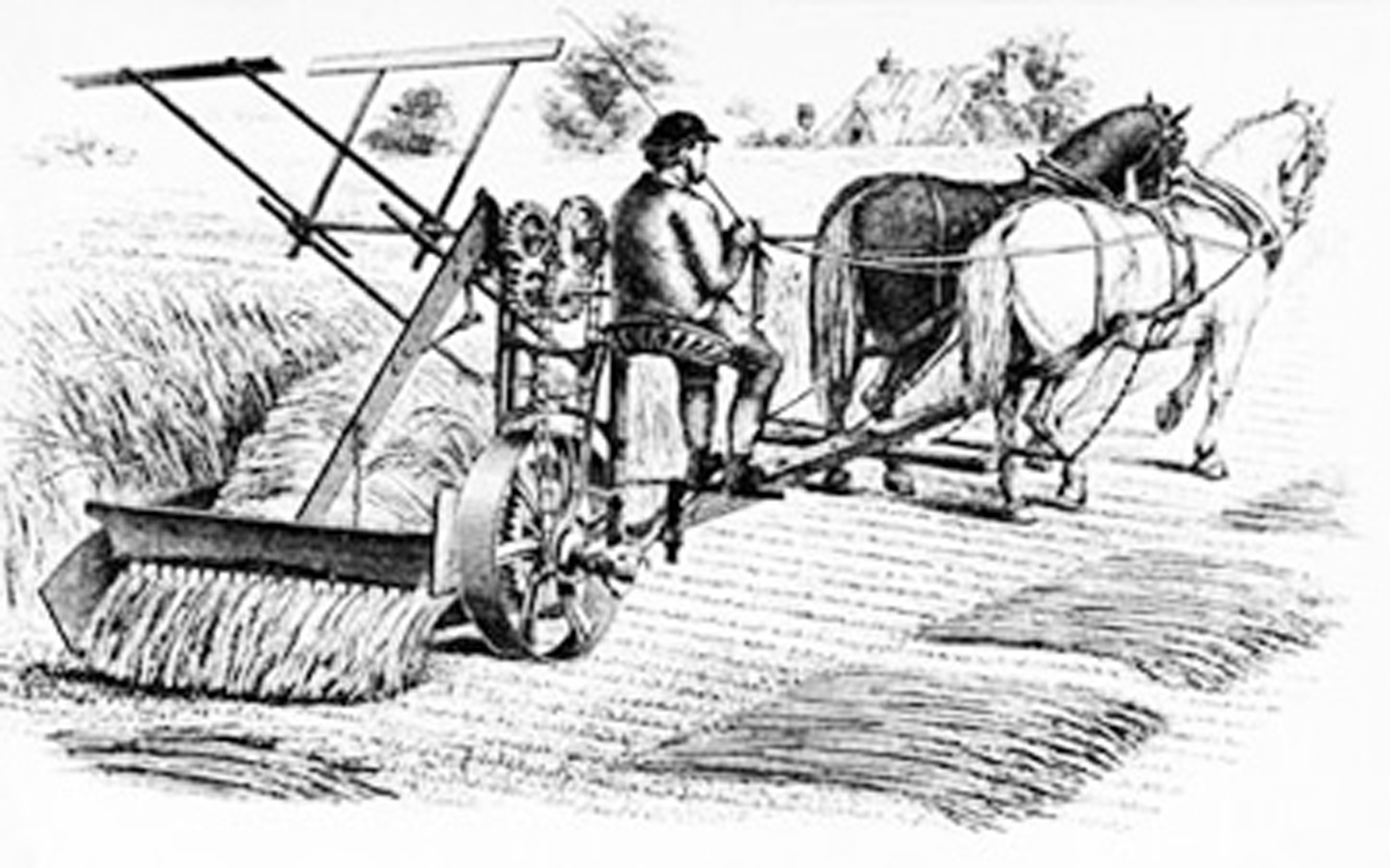

Inventions of Agriculture: The Reaper

Agriculture has been a staple of human society since around 9000 BCE during the Neolithic Era, when humans began developing and cultivating their own food.

For centuries, food production was a slow, tedious process until the invention of agricultural machinery. One such invention was the reaper. Until its time, small grains were harvested by hand, cut with sickles or scythes, hand-raked and tied into sheaves.

While a few had unsuccessfully attempted to create a similar machine, it was Cyrus McCormick who would ultimately be credited with the invention of the first commercially successful reaper in 1831.

McCormick’s invention was a horse-drawn machine used to harvest wheat, a combination between a chariot and a wheelbarrow. He had joined together the earlier harvesting machines into a single, timesaving one. His reaper allowed producers to double their crop size, capable of cutting six acres of oats in just one afternoon. In contrast, it would have taken 12 workers with scythes to do the equivalent in the same amount of time.

McCormick had simply followed in his father’s footsteps. Growing up in Rockbridge County, Virginia, his father had also created several farming implements and even worked to invent a mechanical reaper of his own.

McCormick would patent his invention in July 1834, a year after Obed Hussey had announced the making of a reaper of his own. In 1837, McCormick began manufacturing his machine on his family’s estate.

In 1847, McCormick recognized Chicago as the future of the agricultural machinery industry. The railroad to Galena was nearing completion, the Illinois and Michigan Canal would soon be open, and a telegraph link to the east was coming. So, in 1847, McCormick, together with his partner and future Chicago mayor Charles M. Gray, purchased three lots on the Chicago River and built a factory where they would produce the reaper. It was the first of many industrial companies that would make their way to the area, making Chicago an industrial leader.

McCormick wasn’t done yet. He purchased an additional 130 acres in Chicago in 1871, but the Great Fire of 1871 threatened to destroy his company when the factory burned. It was his young wife, Nettie Fowler McCormick, who pushed the company forward when she went to the site just days after the fire and ordered the rebuilding of the factory. By 1880, McCormick was the largest machinery producer in Chicago and employment reached 7,000, a whopping fifth of the nation’s total.

McCormick joined the companies of Deering and Plano to form the International Harvester Company in 1902. At its height, the company controlled more than 80 percent of grain harvesting equipment in the world. While the Great Depression would hit Chicago’s agricultural industry hard, McCormick’s invention of the reaper forever changed the face of agriculture.

Resources

Carstensen, Fred. (2005) Agricultural Machinery Industry. Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/29.html

Cycrus McCormick, Mechanical Reaper. (2022) The National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved from https://www.invent.org/inductees/cyrus-mccormick

Although the author has made every effort to ensure the information in this article is accurate, this story is meant for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for historical documents.

Farm & Ranch

Scrapie

Barry Whitworth, DVM

Senior Extension Specialist Department of Animal & Food Science Ferguson College of Agriculture

Scrapie is a chronic, progressive disease of the central nervous system that affects sheep and goats. Scrapie is the oldest of the group of neurodegenerative diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE). Some of the other TSE are Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy known as mad cow disease, Chronic Wasting Disease which is found in deer, and Creutzfeldt Jacob Disease which is found in humans. TSE are protein-misfolding diseases that lead to brain damage and are always fatal.

The cause of Scrapie is not completely understood, but evidence indicates that an infectious protein referred to as a prion is responsible for the disease. These infectious prions cause damage to the normal prion proteins found in the brain. The mis-folding of the proteins lead to brain damage and the presentation of clinical signs of the disease. Prions are very resistant to destruction, so once in the environment, they are difficult to remove.

Scrapie is believed to primarily be transmitted by the oral route. Typically, lambs and kids might ingest the prion when they come in contact with the infectious agent through placentas and birthing fluids from infected ewes and does. Older animals may be exposed to the prions this way as well. Colostrum and milk are also sources of prions. Other secretions such as urine, feces, saliva, and nasal secretions may contain infectious prions as well. Once ingested, the prions cross into the lymphoid system. The prions will incubate for a long time usually two to five years before entering the nervous system.

Genetics plays a part in Scrapie infections. Certain breeds are more susceptible to the disease due to genetic composition. Genetic testing is available for producers to help them select breeding stock with resistant genes.

Clinical signs most commonly associated with Scrapie are intense pruritis, ataxia, and wasting. Early in the disease, small ruminant producers may notice slight changes in behavior with sheep and goats infected with Scrapie. Initially, animals may have a staring or fixed gaze, may not respond to herding, and may be aggressive towards objects. As the disease progresses, other clinical signs noticed are progressive weight loss with normal appetite, incoordination, head tremors, and intense pruritis. In the terminal stages, sheep are recumbent and may have blindness, seizures, and an inability to swallow. Once initial clinical signs are notice, death usually occurs in one to six months.

The gold standard for postmortem (dead animals) diagnosing of Scrapie is the use of immunohistochemistry test on brain tissues as well as microscopic examination of brain tissue for characteristic TGE lesions. Live animal diagnosis is possible by testing lymphoid tissues from the third eyelid and rectal mucosa scrapings.

There is no treatment available for Scrapie, so prevention is key to controlling the disease. Following biosecurity protocols is a good starting point for preventing Scrapie. Part of the biosecurity plan is to maintain a closed flock and only buy replacement animals from certified Scrapie free flocks. Producers should limit visitors’ contact with their animals. Sanitation is important in lambing and kidding areas. Manure and bedding contaminated with birthing fluids and placentas should be disposed of properly. Genetically resistant animals should be used for breeding to produce genetically resistant offspring.

It should be noted that there is a novel or atypical form of Scrapie. This disease may also be referred to as Nor98 variant. This atypical version of Scrapie was initially found in Norway. It has been diagnosed in the United States as well. The disease is usually only found in a single old animal in the flock or herd. The brain lesions in atypical Scrapie are different from classical Scrapie. Currently, experts believe that natural transmission of atypical Scrapie is not likely.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been battling Scrapie for decades. According to recent information from the USDA, the United States (US) is close to accomplishing eradication of the disease. In order for the United States to achieve Scrapie free status, no sheep or goats can test positive for classical scrapie for seven years and a certain level of testing needs to be done each year that represents the sheep and goat populations within the country. Small ruminant producers can assist the USDA eradication efforts by contacting the USDA when they have an adult sheep or goat exhibiting clinical signs of Scrapie or an adult animal dies or is euthanized. Producers should contact the Oklahoma State Veterinarian, Dr. Rod Hall at 405-522-6141 or the USDA Veterinary Services at 405-254-1797. This will aid the USDA in reaching sampling testing goals. There is no charge for the collection or testing of the samples for scrapie.

Scrapie is a disease that needs to be eliminated from the US. Once eliminated, the US will have additional export markets for sheep and goat products. Oklahoma State University Cooperative Extension Service has an informative fact sheet on Scrapie. Please visit the Local County Extension Office and asked for fact sheet VTMD-9135 or producers may view the fact sheet online at https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/scrapie.html. Also, the USDA National Scrapie Eradication Program website has valuable information as well at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-disease-information/sheep-and-goat-health/national-scrapie-eradication-program.

References Cassmann, E. D., & Greenlee, J. J. (2020). Pathogenesis, detection, and control of scrapie in sheep. American journal of veterinary research, 81(7), 600–614. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.81.7.600

-

Country Lifestyle7 years ago

Country Lifestyle7 years agoJuly 2017 Profile: J.W. Hart

-

Outdoors6 years ago

Outdoors6 years agoGrazing Oklahoma: Honey Locust

-

Country Lifestyle2 years ago

Country Lifestyle2 years agoThe Two Sides of Colten Jesse

-

Attractions7 years ago

Attractions7 years ago48 Hours in Atoka Remembered

-

Outdoors4 years ago

Outdoors4 years agoPecan Production Information: Online Resources for Growers

-

Farm & Ranch6 years ago

Farm & Ranch6 years agoHackberry (Celtis spp.)

-

Equine7 years ago

Equine7 years agoUmbilical Hernia

-

Country Lifestyle1 year ago

Country Lifestyle1 year agoSay Yes!